Search this section

CURRICULA

- Designing peacebuilding and prevention programmes

- Operational-level Planning for Military - Centre of Gravity and Operational Design

- Implementing Local Ownership in Security Sector Reform (SSR) Missions

- Mediation, Dialogue, Negotiation

- Multi-stakeholder Training in Protection of Civilians in Peacekeeping Missions

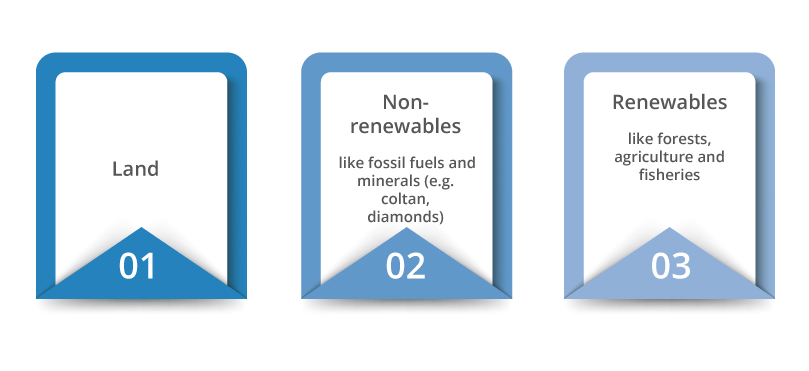

- Conflict Sensitive and Participatory Natural Resource Management in Post-War / Conflict Settings

- Preventing Natural Resource-Based Conflict at the Community Level

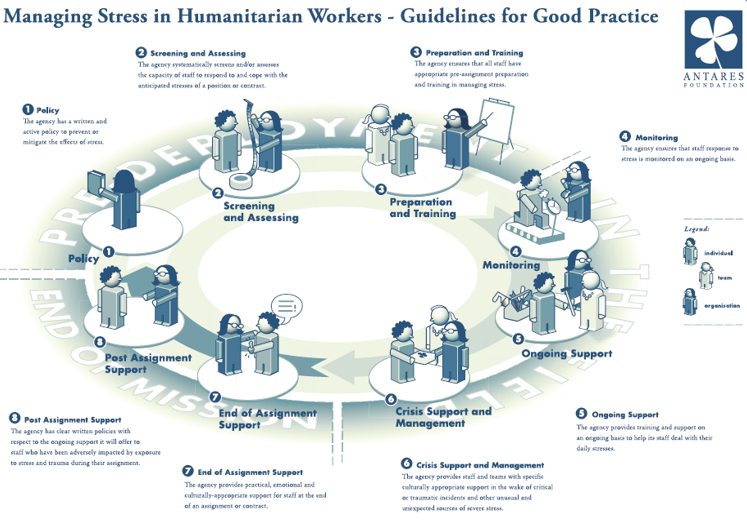

- Self-Care for CPPB Mission Professionals

- Sensitivity in Working with Survivors of Gender-Based Violence

Introduction

Potentially encompassed in a comprehensive preparation curriculum for practitioners operating on programmes and projects in the peacebuilding field, the sub-curriculum on Designing Peacebuilding Programmes (DPP) is a core-competencies course that prepares practitioners to work jointly with the programming and project cycle logic and conflict awareness and sensitivity logic.

There is a gap between the scale of people’s efforts and investment, the huge number of programmes, activities and organisations in the field, and the impact this is all having on peacebuilding and sustainable post-war recovery and stabilisation. This programme has been designed to close that gap. It is practical and operational, designed for policy makers, donors and practitioners, and those dealing with the daily challenges of peacebuilding, development and recovery in areas affected by war and violence.

It draws from across the entire breadth of operational experience, lessons learned and practical methodologies – doing so in a way that has been designed to enable agencies and organisations to go in-depth into their work and how they are doing it, coming out with better designs, better approaches, and with real effects.

At the completion of the Designing Peacebuilding Programmes Course the participants will:

- complete their understanding of the “peacebuilding palette” (a full spectrum of possible peace projects and initiatives) and their respective effectiveness

- be informed and understand a possible model for a full cycle design, including peacebuilding-specific tools and methods

- be able to define and understand the quality criteria of a solid, conflict-sensitive design of a peace programme

- be able to identify and understand the role of different stakeholders not only in the implementation but also in the design of peacebuilding mission

- envision be able to apply with flexibility and to customize some of the tools to concrete cases of their interests and better integrate appropriate and effective design, planning, development, and monitoring and evaluation tools into the work of their organisation/agency

- have achieved an understanding on the main challenges related to design and implementation of peace programme design and ways on how to deal with these challenges.

- refine their skills to work in diverse teams for planning and designing a peacebuilding programme

- demonstrate an interest in engaging in improved programme design in the peacebuilding field.

A number of reasons make this particular sub-curriculum relevant for peacebuilding and prevention missions, the main ones being: 1) need for improved coherence of programming framework among different stakeholders, 2) need for the use of appropriate of peace- and conflict specific planning tools, and 3) need to realize the continuous and systemic nature of programme (re) design process and the key moments in a mission life-time when such a design process should happen as well as the key actors that should be involved in the design process.

- need for improved coherence of programming framework among different stakeholders. Findings of a number of peacekeeping, humanitarian and peacebuilding evaluation reports and related research have indicated the need for the United Nations to focus efforts at improving ability to undertake meaningful, coherent, coordinated and sustainable peacekeeping operations. The Brahimi report for example indicated that, a “contemporary peace operations, that combine a wide range of interrelated civilian and military activities (interposition; disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR); rule of law; institutional building; humanitarian aid; economic reconstruction. Introduction to IMPP UN Peacekeeping makes an integrated and coordinated approach a condition of coherence and success”. Also, a Joint Utstein Study of peacebuilding analysis of 336 peacebuilding projects implemented by Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Norway over a decade identified lack of coherence at the strategic level in what it terms as ‘strategic deficit’, as the most significant obstacle to sustainable peacebuilding

- need for the use of appropriate of peace- and conflict specific planning tools While mission briefings and often project cycle management represents a component of many mission planning courses, what is rare and needed is the embedding of concrete peace- and conflict-specific tools in the programming cycle as well as the emphasis in missions not only on the knowledge (mission brief, mission details) but also the skills and at the attitudes to be consolidated from the moment of mission planning and design, through the re-design during the implementation. Examples of this could include the capacity of conducting comprehensive stakeholder analyses and the attitude/principle of valuing participation from a large number of stakeholders in the mission (re-) design process.

- need to realize the continuous and systemic nature of programme (re) design process and the key moments in a mission life-time when such a design process should happen as well as the key actors that should be involved in the design process. Particularly relevant for missions being implemented in conflict settings where the context is changing frequently and where the decision making on re-alignment needs to be taken several times, the DPP offers the opportunity to train on understanding the systemic, cyclical nature of design of the mission and also to train on the preparedness to undertake several re-design processes during a mission life-cycle.

The programme is relevant mostly in the mission start-up as well as during the implementation of the mission, if the mission mandate includes the flexibility of re-design or renewal of mission planning/ part of the mission activities.

The curriculum could be delivered to multi-stakeholder groups and be relevant to a wide variety of missions, with the emphasis on civilian peacebuilding missions and mixed civil-military mission programming and coordination in a certain setting.

- UN, OSCE, EU, Commonwealth, OAS, AU and ASEAN staff, Deployable civilian experts and field staff of international and national organisations and agencies working in areas affected by violent conflict and war, or in post-war violence-situations

- Senior to mid-level staff and executive officers in national and international aid and development organisations and organisations dealing with peacebuilding, post-war stabilisation and recovery, or working in areas affected by armed conflict

- Staff of international and national NGOs working in the fields of development, human rights, stabilization and recovery, conflict resolution, confidence and security building measures, democratisation, and social empowerment, gender and peacebuilding, and reconciliation and healing

- National and local level politicians in countries affected by war and conflict or with portfolios responsible for issues dealing with peacebuilding, conflict transformation, violence prevention, post-war stabilisation and recovery, reconciliation and healing

- Mediation parties including government leadership and conflict parties and their representatives involved in mediation and negotiation processes

- Mediators and those involved in facilitating and supporting formal and information mediation processes, including back channel negotiations and quiet diplomacy

- Donor agencies, governmental and non-governmental organisations involved in funding, assisting, and capacity building/support operations for peacebuilding, conflict transformation, violence prevention and post-war stabilisation and recovery programmes

- Members of working groups, expert groups and negotiation teams involved in mediation and peace processes, and confidence building working groups

Training institutions /trainers who have received expressions of interests or indications of needs to improve the competencies around planning and conflict-sensitive interventions could benefit from using such a sub-curricula.

Training institutions / trainers engaged as consultants or contractors for strategic planning processes around CPPB missions and operations as well as training institutions /trainers/ policy institutions who want to follow a curricula to determine a country strategy for a specific type of mission are to find the in DPP curriculum a valuable capacity building framework.

Practitioners who have a specific mandate and terms of reference around developing strategic planning processes, programming or project design in the field of conflict prevention and peacebuilding operations can directly benefit for this curricula as a design laboratory that leads them to having a concrete and solid plan for their direct tasks. Practitioners who have the task of monitoring and evaluating CPPB projects/programmes could also benefit from this curriculum.

Development Organisations or Agencies could use the DPP curriculum to train their programming staff as well as a reference framework for the evaluation of existing conflict prevention and peacebuilding programmes.

- Knowledge

- Know the different phases of a project cycle

- Know the steps that take to design a project

- Understand the cyclical, strategic and systemic nature of designing a peacebuilding project

- Skills

- Be able to analyse the design process and derive a list of DO’s and DON’T for the specific context (conflict issue and stakeholders) of the project designed

- Apply the peacebuilding strategic planning model of DPP to different conflict situations Attitudes:

- Demonstrate a real commitment and interest in engaging on a solid design process

- Refine a proactive attitude towards initiating collaborative planning processes

- Knowledge

- Know and understand the concepts of ‘conflict sensitivity’ and the concept, approach and programme planning steps of DO NO HARM

- Skills

- Be able to identify indicators for conflict sensitivity with respect to: project design, programme designing process ; Be able to identify and create risk maps and risk mitigation strategies

- Attitudes

- Demonstrate interest and an integration of the different sensitivities throughout the planning process during the course

- Knowledge

- Understand the difference between mapping, analysis and assessment; Know the main elements and core questions of a conflict assessment process

- Skills

- Be able to apply a series of conflict analysis tools (as a minimum: actor map, conflict tree, sources and pillars, ABC/DSC triangles, conflict timeline)

- Attitudes

- Appreciate the value of a participatory and multi-partial conflict analysis

- Knowledge

- Know the main elements and core questions of the deciding the strategic path of the CPPB project/programme

- Skills

- Know the main elements and core questions of the deciding the strategic path of the CPPB project/programme

- Attitudes

- Demonstrate appreciation about having solid arguments and a strong (backed by data and experiences) rationale behind choices made in a project

- Knowledge

- Know the main elements and core questions of creating a MEAL/ME/MELI plan for a project/programme; Understand the concept and main elements of conflict sensitive monitoring and evaluation; Know the concepts of Peace Writ Large and Peace Writ Little

- Skills

- Be able to create a MEAL plan, Be able to formulate results and impact indicators as well as quality criteria for: a) the design of a project b)the content of a project c) the process of design of a project

- Attitudes

- Commitment especially to the accountability and learning as core components of the ME process, and to conflict sensitivity and do no harm in the evaluation process

- Knowledge

- Know basic concepts of dialogue, feedback, active listening, consensus, confidentiality and collaborative leadership

- Skills

- Group facilitation and dialogue, problem solving, encouraging participation and input from all members of the group; Empathy

- Attitudes

- Value group work and diversity of perspectives; Appreciate the input coming from different conflict perspectives and engage with openness in dialogues on controversial themes

I. PROJECT CYCLE MANAGEMENT

II. CONFLICT SENSITIVITY and DO NO HARM

III. CONFLICT ANALYSIS

IV. PEACEBUILDING STRATEGY/ CHOICES

V. MONITORING AND EVALUATION

VI. MONITORING AND EVALUATION

This curricula links to:

- Introduction to CPPB *

- CONFLICT ANALYSIS / ASSESSMENT *

- STRATEGIC PLANNING/ MISSION PLANNING

- CONFLICT SENSITIVITY *

- PCIA *

- Monitoring/Evaluation/Accountability and Learning in Peace Operations *

* (these courses can be considered pre-requisites when the DPP is offered at Intermediate/Advanced or Expert Level)

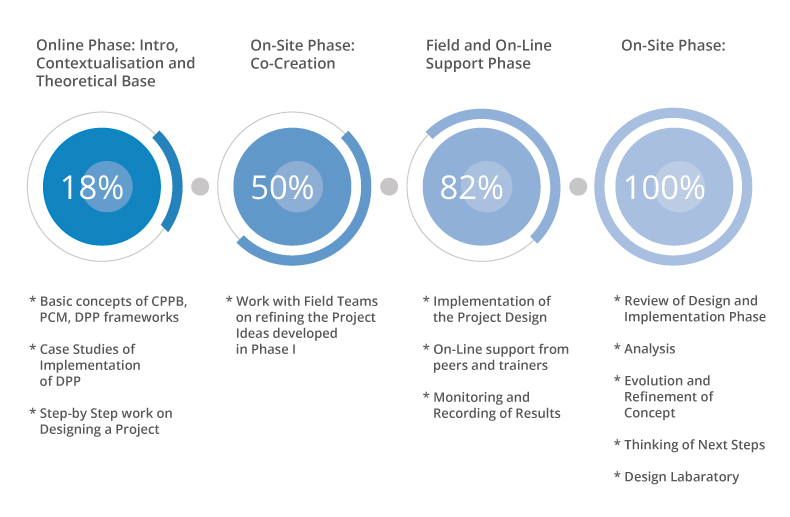

As the same content and knowledge base can be delivered in different formats depending on the time/resource availability, urgency of programming process or motivation of running a solid design process, the DPP can be offered as DPP 1 (one-time, on-site training) or DPP2 (a blended learning process including on-line and on-site phases). The DPP1 curricula is designed for a one-time on-site training.

At the same time, where mission/ participants time allocation allow it could be well delivered in a blended learning setting, named DPP2, including a) an on-line phase including modules on introductions and contextualization, theoretical base and case studies; b) an on-site phase of design and programming co-creation; c) a field-phase where the design in implemented and tested and d) an on-site or an on-life evaluation of design and practitioners sharing of learning and refining the planning model phase;

In either form, the Designing Peacebuilding Programmes curricula includes several different curricular modules described below:

- Module 1 : Peacebuilding Programming and Design: State of the Field, Existing Models, Quality Criteria

- Module 2: The DPP model and possible tools

- Module 3: Peace and Conflict Assessment

- Module 4: Visioning

- Module 5: Strategic Programming Choices: Theory of Change, Scenario Planning

- Module 6: Detailing own Peacebuilding Palette: Action/Activity Planning and Timing, Risk Identification and Mitigation Strategies and resource Allocation

- Module 7: Monitoring, Evaluation and Realignment

- Module 8: Improving Coherence & Strategic Frameworks of CPPB projects/programmes and Evaluating the Design Process.

The methods used to deliver these modules include:

- Interactive presentations; End-of-the-day briefing notes

- Case studies a) presented by the trainer b) chosen by participants and used as examples in the group work, where based on those respective case studies participants are designing own peacebuilding projects/programmes

- Working Groups

- Expert Forum

- Reflection rounds and journaling

- Icebreakers and Energisers connected with the theme and topic of each module and implemented in selected sessions throughout the curriculum

While the training curricula can be adapted to different levels of experience and expertise, it is most appropriate at Intermediate, Advanced and Expert level of practice with project management and peace and conflict work. Elements of basic project design (e.g. PCM, PCIA), definitions of peace, conflict and conflict sensitivity are prerequisites for such a course. The timing of the modules can be adjusted to include such concepts thus depending on the level of previous expertise of participants the duration of implementation of such curricula can be increased with the missing modules.

Beginner / Entry

While the relevance at beginner/entry level is low, at this point DPP curricula can introduce the core elements of strategic and systemic design, can introduce the DPP model together basic elements of PCM (Project Cycle Management) and a few tools of peace and conflict work to be applied. At the beginner/entry level, rather than working with participants’ cases more effective might be introducing case studies of applying the DPP model to concrete situations and having participants work on very detailed-defined case studies.

Intermediate / Advanced

The curriculum is mostly designed for a core / majority group of training participants who find themselves at intermediate/advanced level. This entails having prerequisites of previous knowledge in the areas of peace and conflict fundamentals (knowing and being able to functionally work with different definitions of peace and conflict, being able to define and formulate a conflict/issue, conflict actor maps, PCM, problem trees, GANTT charts, having a basic awareness of conflict sensitivity and PCIA etc). At this level the focus would be on the awareness of the different planning models and then, refining KSA related to concrete tools of analysis, vision setting, strategy and MEAL, adding new, more complex tools to participants’ peacebuilding toolbox (e.g. Integrated conflict tree and DSC triangle) and working on the skills to balance limited resources and time to having a strategic and systemic design process.

Expert / Specialisation

At this level the training would focus mostly on the customized work of practitioners and experts to design own projects and programmes that would be immediately implemented in the field. At this level the curricula’s dominant approach is a training laboratory and expert exchange forum, aiming to derive the best strategic and detailed choices that one could take in conceptualizing a peacebuilding intervention.

Peace and Conflict Sensitivity is directly included in the curriculum, linking the concept of conflict sensitivity, the project planning methodology of DNH to the DPP model as well as through suggesting of conflict sensitivity tools and assessment criteria at each of the different steps of the DPP process. Peace and Conflict Sensitivity is also one of the CORE QUALITY CRITERIA listed for the design of a CPPB project/programme.

Local Ownership is also strongly emphasized in this curricula through: a) the inclusion of PARTICIPATION as one of the CORE QUALITY CRITERIA listed for the design of a CPPB project/programme. Local ownership is also reflected in this curricula through the choice of relevant case-studies and examples, which are, at the time of each course chosen to fit participants’ needs and realities.

For the implementation of the DPP curriculum a mixed-team, mixed-methods approach is the one that provides sufficient diversity and complexity throughout a 5-days to several months process.

Implemented within a mixed team, of practitioners the programme includes methods such as: interactive presentations, case studies and significant amounts of group work on participants’ own cases. The training programme is also complemented by reflection sessions as well as personal development sessions where participants are guided by a coach in their own professional choices often related to the design of the respective programmes. When implemented in the DPP2 model the training includes practical implementation in the field of the design and learning-by-doing approach, with supervision and coaching.

The main innovative aspect consists in the participatory and hands-on approach to training, where participants are owners of the process and work on concrete projects, with the other colleagues being peer advisors. Also the DPP 2 model, with a sequenced approach to training also represents an innovative approach to implementing a training programme. Aside from that a series of methods such as elements of forum theatre, elements of self-care and reflection are introduced and reflect also front of the field tendencies in adult learning and specifically peacebuilding adult learning.

The DPP approach to developing competencies includes a process-focus including the phases of assessment, theoretical reflection and modelling and learning from practice, application for concrete cases, real and realistic design and implementation and evaluation and reflective learning. The DPP curricula proposed would include a blended capacity building approach. As designed at upper-intermediate levels for practitioners it would involve an advanced online assessment and sharing of the mission profile and peace and conflict contexts as well as a guidance/coaching/support phase in the 6- 12 months following which would contain tailored support from trainers/ peers on the implementation of the designed elements into the concrete project/programme. If implemented in the DPP2 version, the approach would even more be rather of consultancy and mentoring nature rather than a classic / academic learning experience.

| Name of the Provider: Institution / Training Centre / Academy | Course Title | Link to Course Outline (if available) | Link to Relevant Publications / Resources / Handbooks / Toolkits used in the course (if available) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PATRIR | Designing Peacebuilding Programmes: Improving the Quality, Impact and Effectiveness of Peacebuilding and Peace Support | patrir.ro | - |

| Title | Organisation / Institution | Year | URL (if available) or Publishing House & City |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designing for Results | Search for Common Ground | 2006 | www.sfcg.org |

| Strategic Peacebuilding: State of the Field | Lisa Schirch | 2008 | www.scribd.com |

| Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners | Mary B Anderson, Lara Olson | 2003 | cdacollaborative.org |

| The Do No Harm Handbook (The Framework for Analysing the Impact of Assistance on Conflict) | CDA (Local Capacity For Peace Project) | 2004 | www.globalprotectioncluster.org |

| Conflict Assessment and Peacebuilding Planning: Toward a Participatory Approach to Human Security | Lisa Schirch | 2013 | Kumarian Press, Boulder, CO, USA |

| Towards a Strategic Framework for Peacebuilding: Getting Their Act Together Overview report of the Joint Utstein Study of Peacebuilding g | Dan Smith | 2004 | www.regjeringen.no |

| Civil Society and Peacebuilding | Thania Paffenholz | 2009 | www.sfcg.org |

The DPP programme is normally a multi-stakeholder programme, yet some considerations as to when it is implemented for specific stakeholders are presented below:

Civilian / NGO

When implemented in Civilian NGO contexts the DPP programme should pay particular attention to models such as: Civil Society Role in Peacebuilding and Effectiveness of Civil Society actions, as well as to the ways of engagement, from a civil society point of view across tracks. Also at civilian, NGO level it is important to mark and discuss the coherence and strategic engagement of civilian actors, as the lack of coordination at the least without mentioning collaboration has been identified as one of the major gaps that are to be covered. The mapping of parallel initiatives as well as doing a PEACE and CONFLICT profile of the situation are activities that are to be implemented and emphasized.

EEAS / Diplomats / Civil Servants

When implemented at the diplomatic level, the DPP programme should involve an emphasis on policy coherence in the sense of transposing into the projects and programmes designed of principles that are embedded into local, national and international policies (such as Country Strategies, Paris Declaration, Peace Agreements etc). At this level it is important also to illustrate and reflect concrete mechanisms of local ownership and as in the previous cases the realistic benefit of cross-track programming and implementation of programmes.

Military / Armed Forces and Police

When customised for Military, Armed Forces and Police the DPP Programme includes at the beginning a clarification in terms of terminology of peacebuilding- peacekeeping, as these are terms used interchangeably often in these spheres as well as an emphasis on the complexity of peacebuilding intervention and the emphasis on scenarios and preparedness to take own decisions which are not always specified in a previously-written scenario. The aspect of Do No Harm and self-awareness and self-care are also innovative aspects that can be included in a DPP-programme adapted for these specific stakeholders.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

This sub-curricula is facilitating one week long Operational-level Planning course, focusing on the two key planning concepts – Centre of Gravity and Operational Design. Operational-level planning is a military planning with the purpose to design major operations and campaigns. Planning of military operations is very complex exercise, particularly, when plans have to address Peace Building and Conflict Prevention missions. These types of Crisis Response Operations are characterized by complexity of the operational environment, which is composed of many layers of interrelated political, military, economic, social, information and infrastructure factors. The relations between causes and effects very seldom are clear thus complicating the understanding of the roots of the problem. Furthermore, desired conditions in such operations mostly can be achieved only through synchronized civil-military actions.

Regardless the scope and intensity of military operation, the key concepts applied during the operational-level planning include: Centre of Gravity (COG) analysis and Operational Design. Both concepts complement each other and offer a way for the planners to give a structure to complex problem, so that it is possible to identify actions leading to the desired conditions. Capability to apply those concepts is one of the key competencies of every staff officer.

COG analysis and operational design are two concepts the rest of the operations planning and execution processes in Western military culture are based upon. COG analysis allows identifying the key attributes of the main actors involved in the crisis or conflict, whether operational design is used throughout the operation to communicate the envisioned role of the military, develop and adapt operational plans, synchronize actions and assess the progress of the operation. The overall aim of this sub-curriculum is to educate military planners to create solutions to the complex operational level problems by applying Centre of Gravity Analysis and Concept of Operational Design.

Upon completion of the course students should be able to:

- Explain NATO Crisis Management Process

- Explain phases and processes of NATO operational-level planning process

- Contribute to Comprehensive Preparation of Operational Environment

- Explain the DO NO HARM Analytical Framework, its similarities, differences with NATO planning process

- Apply Factor-Deduction-Conclusion construct of analysis of operational environment

- Explain the overall purpose of the COG analysis

- Understand the importance of solid CoG analysis in ensuring the achievement of desired effects

- Explain the linkage between COG analysis and the process of assessment of the operational environment

- Explain the theoretical background of Center of Gravity concept

- Examine attributes of COG, including critical capabilities, critical requirements, and critical vulnerabilities

- Describe the different methods of COG analysis

- Apply Centre of Gravity concept for planning of full spectrum of military operations

- Explain the purpose of the Operational Design

- Understand how military operational design is connected with objectives of other stakeholders and actors of the operational environment, particularly, when designing operational design for peace building missions

- Explain the relation between CoG, Operational Design, Mission Objectives and Impact on Peacebuilding, Humanitarian operations

- List and describe the main components of the operational design, including: a) Operational Objectives b) Decisive Conditions c) Desired Effects d) Actions e) Lines of Operation f) Phases of Operation g) Decision points

- Explain different methods for developing operational design

- Develop operational design

Operational-level planning is conducted before deployment of the military contingent to the area of operations as well as during the execution of mission. Capability of military personnel to apply COG analysis and explore the concept of operational design is enabling application of military assets during full spectrum of military missions, including conventional military operations as well as crisis response operations, including Conflict Prevention, Peace-making, Peace Enforcement, Peacekeeping and Peace Building, counter regular activities and support to civil authorities.

The importance of the comprehensive mission planning is continuously highlighted by policy makers and practitioners.

The training is not specific to a type or phase of a mission, it could be used also in the context of mission assessment and evaluation.

This training is applicable for the military personnel as well as civil servants who might be involved into the planning and/or execution of multinational operations at operational or component level headquarters. This course is applicable for decision makers and staff officers and civil servants. If possible, training audience should be composed of representatives from military and civilian institutions and represent various backgrounds and experiences.

The content of the SC can be applied for pre-deployment training as well as during the mission in order to increase collective and individual operational-level planning performance. When delivered during the mission this SC should build upon pre-deployment training and be delivered under the approach of “adjusting”, “monitoring” “evaluating” and “learning”.

This type of course is necessary for everyone going to participate in the mission planning, particularly in the military, but also among the civilians.

| Following key competencies are targeted by this course: | K | S | A |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explain NATO Crisis Management Process | x | ||

| Explain NATO Operational Level Planning Process | x | ||

| Apply Factor-Deduction-Conclusion construct of analysis of operational environment | x | ||

| Explain the overall purpose of the COG analysis | x | ||

| Explain the linkage between COG analysis and the process of assessment of the operational environment | x | ||

| Explain the theoretical background of Center of Gravity concept | x | ||

| Examine attributes of COG, including critical capabilities, critical requirements, and critical vulnerabilities | x | ||

| Describe the different methods of COG analysis | x | ||

| Apply Centre of Gravity concept for planning of full spectrum of military operations | x | ||

| Explain the purpose of the Operational Design | x | ||

| Explain the relation between Operational Design and COG | x | ||

Describe and use the main components of the operational design, including:

|

x | x | |

| Explain different methods for developing operational design | x | ||

| Develop operational design | x | ||

| Explain the basic principles and methods of the operational assessment | x | ||

| Assume responsibilities during the planning process | x | ||

| Contribute to the team work | x | ||

| Maintain non-judgmental and respectful attitude | x | ||

| Recognize the benefits of diverse understanding of the problem/solution | x | ||

| Maintain cultural awareness | x | x | x |

| Describe here in detail the core competencies to be covered by this sub-curricula. Develop each as 1 paragraph or more. Put the ‘title’ / |

This curricula is a supplementary to the courses introducing NATO operational level planning process. This course can be taken before or after attending operations planning courses for operational or strategic level planners conducted by NATO School Oberammergau, Finish Defense Forces International Center or by other national or international professional military institutions. Some links to such courses are provided later in this paper.

Day 1 and 2 NATO CRISIS MANAGEMENT PROCESS

The aim of the SC is to familiarize training audience with the NATO Crisis Management Process, phases and key concepts of the Operational Level Planning, DO NO HARM analytical framework, Comprehensive Preparation of Operational Environment and process and factor – conclusion - deduction construct of analysis.

Teaching methods: lecture, small group activity (max 10 persons).

Small group assignment

Within given scenario as a member of planning team conduct Comprehensive Preparation of Operational Environment and present key findings. Apply factor-deduction-conclusion construct of analysis. Present your findings on Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure and Information domains.

Day 3 and 4: COG ANALYSIS

The aim of the teaching activity is to introduce the audience with the overall purpose of the Center of Gravity (COG) analysis by explaining linkage of the COG concept with other operational planning and management processes and concepts, particularly, analysis of the operational environment and operational design. Introduce the training audience with the attributes of COG, including critical capabilities, critical requirements, and critical vulnerabilities. Explain the theoretical background of Center of Gravity concept, starting with the origins of the concept in Clausewitz’s writings, and covering the various interpretations and methods applied to identify and analyse the concept. Describe the different methods of COG analysis.

Teaching methods: lecture, small group activity (max 10 persons).

Small group assignment

Within given scenario as a member of planning team Apply Centre of Gravity concept for planning of military operation

Day 5 and 6: OPERATIONAL DESIGN

The aim the teaching activity is to introduce the training audience with the purpose of the Operational Design and familiarize with the main components of the operational design, including:

- Operational Objectives

- Decisive Conditions

- Desired Effects

- Actions

- Lines of Operation and Options

- Phases of Operation

- Risk Assessment and Decision points

Explain the relation between Operational Design and COG and demonstrate different methods for developing operational design, effects/actions matrix and effects overlay. Explain the basic principles and methods of the operational assessment.

Teaching methods: lecture, scenario planning/simulation small group activity (max 10 persons).

Small group assignment

Within given scenario as a member of planning team develop operational design, including effects/actions matrix and overlay.

The duration of the syndicate tasks and lectures are tentative and depends on various external and internal factors, including complexity of the scenario, subject matter knowledge of the training audience and availability of the time.

This is one of the most important sections of the sub-curricula presentation. Here, you should go into detail on the modules / content to be covered in this sub-curricula. Identify and describe each one in at least a paragraph narrative text.

| Beginner / Entry | This course might be applicable for beginner / entry level participants, primarily civil servants with no previous operational planning experience |

|---|---|

| Intermediate / Advanced | This course is primarily intended for intermediate level planners, who has some experience in operational level mission planning and execution |

| Expert / Specialisation | This course can be incorporated into Expert/ Specialisation courses designed also for Policy Advisers within NATO/CSDP and other bodies |

The sensitivity to diverse learning needs is important here. Some audiences are very mixed in terms of knowledge, experience and the other characteristics. To make sure that all of them are on the same page, it is recommended to use the evening-out courses. Particularly useful may be those provided by the ADL means.

Local ownership sensitivity is very important for the peacebuilding operation planning, a part of the teaching should concern integrating this perspective into planning of operations. Cultural sensitivity has been identified as one of the major thematic gaps especially in military operation planning (quote 3.2 report p. 40)

Local ownership sensitivity is very important for the peacebuilding operation planning, a part of the teaching should concern integrating this perspective into planning of operations. Cultural sensitivity has been identified as one of the major thematic gaps especially in military operation planning (quote 3.2 report p. 40)

When delivering this SC one or several of the following approaches can be undertaken:

- E.g. Multi-stakeholder, participatory learning

- E.g. Case-based learning

The methodology is that of a theory-application learning including the following methods:

- LECTURES

Due complexity of the teaching subjects, for the teaching of the theoretical parts of curricula it is recommended to apply lecture/discussion method of teaching.

- SCENARIO / SITUATION presentation + Scenario-Based Planning

The scenario (problem context of the practical part of the learning activity) is very important part of this course. The scenario has to represent relevant problem sets to the training audience to keep them engaged. It is very useful to develop the storyline and the scenario by using e-tools. This allows to inserting video and audio media to visualize the factors of operating environment and planning problems as well as allows training audience to get familiar with the scenario before active class engagement.

- GROUP WORK ; Both in the analysis and development of case studies and scenarios and when in the training room participants with different future missions take part, small group teaching activities are very effective to gain concrete experience regarding all aspects of desired competencies, including skills, knowledge and attitudes.

PeaceTraining.EU has identified several ‘cross cutting themes’ which are important to integrate across peacebuilding and prevention curricula. Please show how these themes may be specifically integrated into this sub-curricula.

The mission planning SC builds upon a significant body of knowledge and practice developed in NATO, CSDP and country operations, innovation in this context and with respect to the training content could include:

- Mixed civil-military training teams where the shared capacities and joint aspects of the mandate can enforce each other and sector-specific gaps can be covered through complementarity. Multiple-perspective operation planning: looking at the planning process not only through the lenses of the mission (mandate, leadership, members) but also through the lenses of the local population, other parallel missions etc.

- Considerations in the mission planning module are also given together with the Do No Harm module to the aspect of “greening missions”

- Using technology: various visual media tools can be used to introduce the training audience with the scenario settings and/or some aspects/challenges of operating environment, for example, short media reports can be used to highlight humanitarian problems in the operations area.

Are there new issues / questions / challenges being addressed in this area of sub-curricula (peacebuilding and prevention interventions-work-programming) which would be important / interesting / useful to mention. What are they? Describe them.

In police missions and other fields ‘competency’ and capacity building include more than in-the-room training. UN missions also provide pre-deployment ‘exams’ at times or tests, or, in the case of police, field-based accompaniment / mentoring. Are there approaches to developing competency / expertise in this curricula additional to ‘training’ which should be considered / listed.

In additional to training this SC could include:

- In-field coaching and mentoring

- Peer support teams and webinars

- Action oriented research: producing through the intentional recording of operational planning models used an integrated model for CPPB operations planning for military and mixed teams

| Name of the Provider: Institution / Training Centre / Academy | Course Title | Link to Course Outline (if available) |

|---|---|---|

| NATO School Oberammergau | ADL 131 Introduction to Comprehensive Operations Planning Directive | jadl.act.nato.int |

| NATO School Oberammergau | ADL 132 Strategic Comprehensive Operations Planning | jadl.act.nato.int |

| NATO School Oberammergau | ADL 133 Comprehensive Operations Planning Course (COPC) | jadl.act.nato.int |

| NATO School Oberammergau | ADL 134 Commander and Staff in Comprehensive Operations Planning and Decision-Making | jadl.act.nato.int |

| NATO School Oberammergau | ADL 134 Commander and Staff in Comprehensive Operations Planning and Decision-Making | jadl.act.nato.int |

| NATO School Oberammergau | S5-54 NATO Comprehensive Operations Planning Course | www.natoschool.nato.int |

| Finish Defense Forces International Center | NATO Comprehensive Operations Planning Course | puolustusvoimat.fi |

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

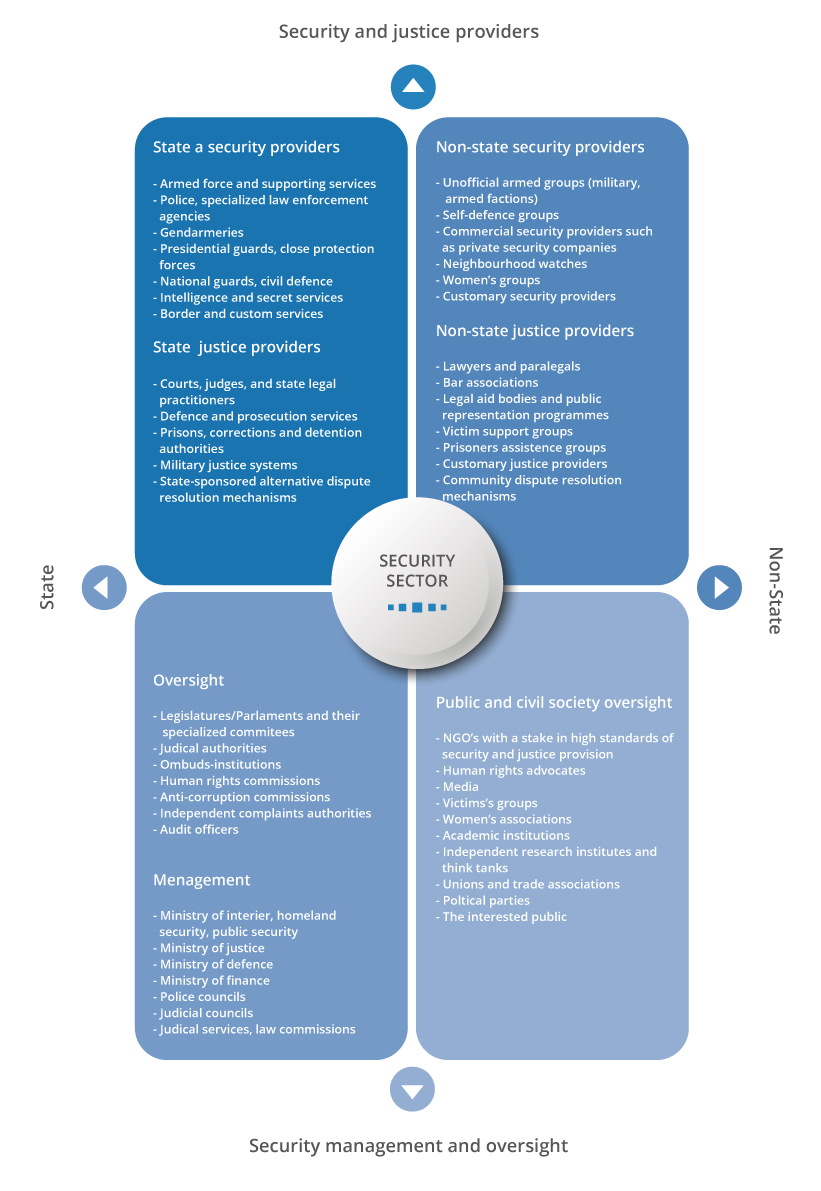

According to the OECD-DAC, Security Sector Reform (SSR) means transforming the security sector, which includes all the actors, their roles, responsibilities and actions, so that they work together to manage and operate the system in a manner that is more consistent with democratic norms and sound principles of good governance, and thus contributes to a well-functioning security framework (OECD DAC). The United Nations refers to security sector reform (SSR) as “a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the State and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law”.

SSR is increasingly recognized as one of the key methods for international donors to contribute to security and development in conflict-affected and fragile states (OECD, 2007) . SSR, through state-building, institutional reform, advising, monitoring, mentoring, and training, has hence become a key policy of international peace and security actors such as the UNSC (2014) and the EU (Joint Communication, 2016) (see Box 1). The EU in particular takes on a range of SSR tasks through the use of Common Security and Defense Policy Missions, such as the police reform missions in DR Congo and Mali, and the training missions in Somalia and Libya.

Box 1: Importance of local ownership in international policy documents

UNSCR 2151: “Reiterates the centrality of national ownership for security sector reform processes, and further reiterates the responsibility of the country concerned in the determination of security sector reform assistance, where appropriate, and recognizes the importance of considering the perspectives of the host countries in the formulation of relevant mandates of United Nations peacekeeping operations and special political missions;”

EC Joint Communication of 2016: “‘National ownership’ goes beyond a government’s acceptance of international actors’ interventions. Reform efforts will be effective and sustainable only if they are rooted in a country’s institutions (including through budgetary commitment), owned by national security and justice actors, and considered legitimate by society as a whole. This means that national actors should steer the process and take overall responsibility for the results of interventions, with external partners providing advice and support.”

International policy documents on SSR uniformly stress the importance of local or national ownership in reform processes to ensure sustainability of the reforms and local support (EU, 2016; OECD, 2007, 2008 ; UNSC 2014).While in the rhetoric of the missions national ownership and local ownership are often overlapping terms referring to the inclusion of national (mainly state) institutions in the SSR process, this SC takes a more comprehensive approach to ownership including grassroot engagement as well as a strongly aware and critical view of different participation levels (see Arnstein, 1969).

Local ownership of SSR means that the reform of security policies, institutions, and activities in a given country must be designed, managed, and implemented by local actors rather than external actors” (Nathan, 2008) . Nonetheless, in practice, local ownership has often been raised as a key gap in SSR policies. Merlingen & Ostrauskaite (2005) have, for instance, pointed out the hierarchical and non-egalitarian nature of EU police reform in Bosnia. More recently, Ejdus (2017) and Jayasundara-Smits & Schirch (2016, pp.23-24) point out that the meaning and implications of local ownership continue to be a challenge for EU-CSDP missions.

Given the importance of Security Sector Reform missions and projects by international donors, as well as the continued challenges with regard to the implementation of local ownership principles, the PeaceTraining.eu project has developed this sub-curriculum on ‘Implementing local ownership in Security Sector Reform missions’.

While local ownership is one of the core principles of SSR, practicing local ownership often remains a challenge for many practitioners involved in project management, monitoring, mentoring, advising, and training tasks to support SSR in third countries. This course responds to this challenge and is designed to train practitioners on how to implement local ownership to ensure effective SSR, based on the principles of local ownership, legitimacy, human security, and democratic accountability. Effective implementation of SSR requires technical expertise (e.g. police, judiciary, military), but using this expertise to support local change processes also requires behavioural changes of technical experts. This course focuses on these behavioural processes and is aimed at delivering the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to implement local ownership and provides critical insights in the factors that inhibit or support local ownership in SSR operations (missions/projects).

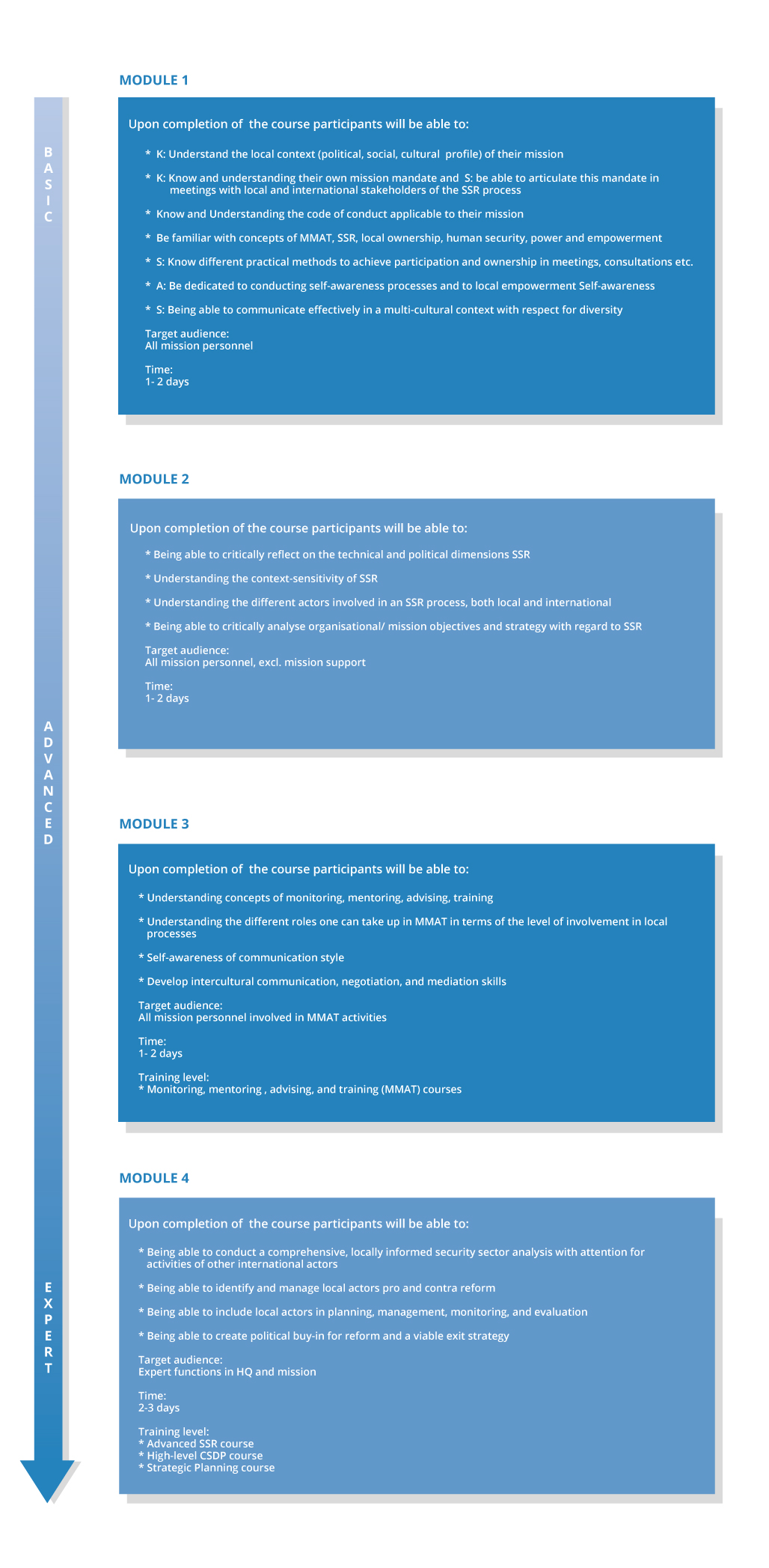

The curricula includes different modules which can be implemented as a corollary to existing pre-deployment and SSR courses in the CPPB training field. Basic, Advanced, and Expert-level modules are designed to be targeted at specific stakeholder audiences according to their function in the SSR operation (incl. mission support, management functions, monitoring, mentoring, advising, and training (MMAT) functions, project design, monitoring, and evaluation positions). Figure 1 below indicates the core competencies for implementing local ownership necessary within an SSR operation and which are developed in the course (Additional competencies for implementing local ownership can be acquired through other courses/recruitment practices e.g. local language skills).

Table 1: The ASK model for implementing local ownership in SSR missions and projects (with module details)

| Attitudes: All modules, cross-cutting | Knowledge | Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for diversity | Local history, politics, economy (M1) | Intercultural communication, active listening (M1,2,3,4) |

| Inclusivity | International policy documents (UNSC 2151) (M1) | Dialogue and networking (M3,4) |

| Empathy | Mission mandate (M1) | Monitoring, Mentoring, Advising, and Training (MMAT) (M3) |

| Equality | Code of conduct (M1) | Political communication, negotiation and mediation (M3, 4) |

| Non-violence | Concepts of human security, SSR, local ownership, MMAT (M1,2) | Working with translators (M3) |

| Social responsibility | Understanding context-sensitivity SSR (M1,2) | Inclusive mission planning, implementation, and evaluation (M4) |

| Patience | Understanding technical and political dimensions reform (M1,2) | Identifying and managing relations with local and international SSR actors (M2,3, 4) |

| Respect for democracy, rule of law, human rights | Understanding existence of formal and informal institutions (M1,2) | Stakeholder analysis (M2,3,4) |

| Understanding need to involve non-state actors (M1,2) | Organizational Change management (M3,4) | |

| Self-awareness (M1,2,3,4) |

Local Ownership has been identified as a major gap in CPPB project, programme and mission implementation as well as in CPPB training (D.3.2., p.38). Indeed, while many practitioners have become aware of the concept, the actual implementation or ‘how to’ of local ownership remains insufficiently addressed in training, and hence, insufficiently practiced on the ground. While the implementation of local ownership can also be hampered by lack of political will, this SC is specifically aimed at improving the skills needed for implementing local ownership.

Furthermore, the following arguments support the importance and need for this SC:

- Effective implementation of local ownership in SSR missions is fundamentally dependent on the daily behaviour of in-mission staff with their local counterparts, including state actors in different hierarchical positions as well as non-state actors, including community representatives and civil society organizations.

- These interactions are dependent on staff members’ knowledge of the local security sector as well as their mission objectives, but also of their attitudinal approaches towards interacting with local counterparts and their skills in rapport-building and involving local owners. Many SSR mission staff are experts in their field, but need to adapt to their supportive rather than implementing or executive role in the field. This requires training in itself.

- An increasingly high level of complexity in considering SSR missions including consideration and coherence with other national policies regarding human rights and gender, transitional justice, DDR, anti-corruption measures, child and women protection etc, requires an increasingly high level of complexity in training to mirror the programmatic ambitions of the EU, UN and OSCE as institutions leading SSR processes in different regions

The training modules are all aimed at staff leaving on SSR missions, yet these are intended to have different levels of experience as well as functions. SSR missions and projects can take on different forms and sizes, but often require the field presence of staff with different experiences and job requirements. For instance, a mission aimed at training military and police also requires the presence of administrative support staff within the mission (HR, finance, logistics etc.). Module 1 is aimed at all these international mission staff and includes basic generic competencies training. The module can also be used to train staff deployed to non-SSR missions, for instance. Other modules are more advanced and focus specifically on local ownership in SSR and are aimed at personnel who are involved in implementing the SSR tasks of the mission. They do, however, build further on Module 1 competencies. Training organizations can target the modules to specific stakeholders, some of which with little to no mission experience, and some who have substantial experience but wish to sharpen their skills or prepare for new, advanced functions, thus these modules can be delivered during pre-deployment or /and as in-mission support.

The Training modules are aimed at different target groups depending on their levels of experience:

- Module 1: All personnel active in the field in a CPPB mission/project/operation: personnel who are engaged in the SSR tasks of a specific mission as well as mission support staff. Hence, all staff that represents the mission and the organization on the ground.

- Module 2: All personnel directly involved in the implementation of the SSR objectives of the mission (excluding HR, administration etc.)

- Module 3: personnel engaged in MMAT activities or staff who are engaged in day-to-day contact with local counterparts.

- Module 4: personnel involved in SSR mission design, management, monitoring, and evaluation, both in the field and in foreign HQs

Many trainings exist in Europe which focus on Security Sector Reform and excellent training materials have been developed and are built on in the curriculum (see bibliography below). Nonetheless, learning ‘how to do local ownership’ and going beyond an understanding of the concept and its principles continues to be a challenge for practitioners. This course is aimed at understanding, but principally applying local ownership as a process with the cross-cutting objective of attitudinal development.

This skill-based learning relies on adult learning principles and participatory methods by focusing on exercises and applications. Trainers and training institutes can build on the proposals in the curriculum to adapt or add to current trainings and are introduced to new competence-based approaches and exercise ideas Thus this SC is relevant and can serve as guidance for those training institutions and trainers with previous engagement in training on SSR who wish to implement practical and practice-oriented training programmes in the areas of SSR.

Through its highly practical nature and focus on developing skills and attitudes relevant and useful in concrete field operations, this SC is particularly relevant for practitioners and deployment organisations. Furthermore, practitioners and deployment organisations/agencies are invited to become involve in a peace training community of practice where this SC is ‘live’ developed and present as an action-oriented research and practice.

The curriculum and its stakeholder-specific modules will make SSR practitioners more effective in the field and support sustainability of donor actions by implementing local ownership in practice. It will train SSR experts to become mission planners, monitors, mentors, advisers, and trainers in local contexts and ensure their adjustment from their role of executive expert to supporter of local actions.

Figure: Stakeholder-specific modules for implementing local ownership in SSR missions

The 4 proposed modules can be implemented as sub-curricula or corollaries to existing SSR courses, which can include more detailed knowledge of the organization for which one is working for instance. In the EU context, existing courses can provide detailed training on EU (CSDP) structures and rules with regard to SSR missions, while the sub-curricula modules are used to delve deeper into the subject of the guiding principle of local ownership.

The following sub-curricula may be directly linked (as pre-requisites, further professionalisation or complementary) to the IMPLEMENTING LOCAL OWNERSHIP IN SECURITY SECTOR REFORM (SSR) MISSIONS sub-curricula when developing more comprehensive training programmes or seeking to integrate in development of core competencies and operational capabilities in this field:

- Mission Leadership

- Do No Harm

- Monitoring, Evaluation of Peace Missions

- Dialogue, Peace Processes and Policy Planning

The curriculum exists of 4 modules which are categorized as basic, advanced, and expert-level.

Module 1 is the most basic and is aimed to provide mission personnel with the necessary generic knowledge, skills, and attitudes to function effectively and principled in a SSR mission. It targets all mission staff from the principle that all staff represent the organization and that their behaviour can impact the overall effectiveness of the mission. CPPB staff are expected to adhere to certain values and inter-relational behaviours that correspond with the principles of local ownership and peacebuilding in general. The learning objectives correspond closely to those of pre-deployment courses, yet aim to strengthen their attainment by developing further participatory approaches to learning and the emphasis is on awareness on the importance and possibilities to practice local ownership in missions.

Module 2 is more advanced and deals specifically with the subject of local ownership, its complexities and nuances. Participants will take up key political functions in the SSR mission or roles as MMATs. The module is to a large extent aimed at understanding and knowledge, but also at critically reflecting on local ownership practices, including their context specificities, and how political objectives can undermine local ownership principles. Participants should also have a good understanding of the wider societal scope of SSR and the need to focus beyond state actors as well as at national policies that do not fall strictly under SSR yet have strong interlinks with this theme. These complexities are specifically addressed by reference to concrete case examples, drawing on experiences from experts and training participants.

Module 3 focuses on those practitioners who will be in engaged in frequent interaction with local counterparts. The aim of this module is to focus deeper on the tasks and different expectations of monitors, mentors, advisers, and trainers, and to foster intercultural communication competences,including deep culture awareness, DNH’s IEMs , active listening, probing, working with local translators, body language, and MSH dialogue negotiation and mediation. The module is mainly exercise-based (e.g. role-plays and simulations) and deepens the knowledge of the self and the participant’s interrelational behaviour, and supports attitudinal developments (e.g. respect for diversity, patience, equality, empathy)

Module 4 is aimed at those practitioners responsible for designing, managing, reporting, and evaluating SSR missions. These experts are trained to support local actors in designing their SSR reform objectives at the strategic level, which requires in depth knowledge of the local security sector and its challenges as well as successes (e.g. needs assessment and stakeholder analysis). Furthermore, participants are equipped with the tools to ensure and recognise through specific indicators local ownership throughout the project duration while also safeguarding their organizations’ principles of democracy and human rights protection. These tasks require advanced communicational and negotiation skills to be able to pick up on local signals that indicate the need to adapt the reform process or the way in which it is conducted.

| Course Levels | |

|---|---|

| Beginner / Entry | See Module 1 |

| Intermediate / Advanced | See Modules 2 & 3 |

| Expert / Specialisation | See Module 4 |

The 5 sensitivities model developed by PeaceTraining.eu are highly relevant for this sub-curricula:

- Peace & Conflict Sensitivity: training participants will recognise that SSR processes can never be successful if they are not context and conflict-specific and if they are driven from the top-down (from the international level to the local context or from the state-level to the population-level) rather than designed following inclusive and participatory procedures. Participants will, however be introduced to major possible differences between conflict settings and how this affects SSR and local ownership missions. This enables them to compare their own mission and case with others on relevant indicators, without being given prescriptive instructions on how to handle specific cases. These aspects are included throughout the four modules in different levels of complexities.

- Cultural sensitivity: cultural sensitivity is one of the crucial aspects of this training. The training is expected to train participants in cultural (self-)awareness and communication, instil them with respect for diversity, and the input from locals. All these sensitivities should not only be part of the curriculum but also reflected in the classroom, for example by including local voices and experiences in the classroom (presence, virtual or real, of local SMEs), by ensuring that interlocutors are aware of possible biases and critically picking up on participant and SME interventions which touch on cultural sensitive issues.

- Gender Sensitivity: gender sensitivities should be mainstreamed throughout the course. For instance, in specific cases, the role of women in the security sector can be analysed and compared. The role of women can also be discussed when debating the principles of international practitioners and how they can differ from local cultures. Yet gender sensitivities should also be discussed in skills-training as intercultural communication can differ according to the gender and societal characteristics of the local actor. Gender lenses are crucial in MMAT activities as well as in mission design, monitoring and evaluation. While local actors should be involved in these processes, it is important that participants learn that ‘local actor’ is a generic category and that specific local actors (including women, children, marginalized populations) require specifically adapted inclusion processes.

- Trauma sensitivity: participants to the training can have acquired prior experiences in their work and in specific conflict-affected settings which they consider traumatic. Trainers should be aware of possible re-traumatization when discussing specific cases, showing particular images and witness testimonies etc. they should ensure this safety check throughout the training, including SME lectures, and be wary of signs of trauma among participants to the training.

- Sensitivity to Diverse Learning Needs: trainers should be wary of people’s diverse preferences in learning for group work, individual work, lectures, and other activities. Training should be carefully planned and ensure variation in types of learning activities and in the use of materials in the classroom and through e-learning by distributing key texts, podcasts, video’s etc. Many courses in CPPB predominantly make use of lecturing activities, however, which creates gaps in skills-development and participatory or adult learning approaches. By focusing on exercises, engagement, and skills, this sub-curricula addresses these gaps in CPPB and SSR training in particular.

The methodology and approach to training is a crucial aspect in the design of this curriculum. It takes the approach that adult learning and participatory learning approaches are most suitable to learn skills-based competencies and this is exactly what is aimed at in ‘Implementing local ownership in SSR missions’. Below we discuss in detail for each module the core and sub-learning objectives and methods to achieve them by taking into account the field’s need for more interactive learning approaches (see D3.5.).

MODULE 1: learning objectives and training approaches

1. Understanding the concepts of local ownership, SSR, Human Security and MMAT:

- Acknowledging that there is no one definition and understanding around some of these concepts especially local ownership and SSR which continue to undergo conceptual evolution and contestations among various organisations, practitioners and academics (Donais 2008). Ultimately influencing how local ownership and SSR are implemented by different organisations.

- Being familiar with key policy documents on local ownership in SSR processes (UNSC 2151, EU 2016, OECD Handbook) and key conceptual differences, including between ‘local’ and ‘national’ ownership, as well as the human security shift in SSR

- Recognising that although a highly contested concept, local ownership is at the centre of SSR, and all major CPPB organizations adhere to this principle.

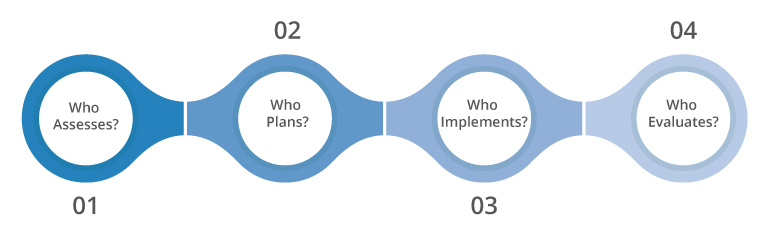

- To understand the concept of local ownership, Schirch and Mancini-Griffoli (2015 p 18) highlights four key questions that ought to be answered:

Responding to and assessing these questions, will enable personnel to clearly understand the interlinkages and complexities surrounding the conceptualisation and practice of local ownership

- Understanding that local ownership should not be limited to state or national level engagement but should transcend to the community level to include other non-state actors and practices (human security)

- Understanding that human security is an integrated and multidimensional approach to security moving beyond traditional military mechanisms to emphasising the interlinkages between development, human rights and security. It aims to enhance human liberty and survival by creating the necessary social, economic, political, security and cultural conditions vital to improving people’s quality of live (UN Human Security Unit 2009)

- Understanding the interlinkages between local ownership, SSR and human security. Whiles SSR focuses on security reforms, human security expands further to include development and human rights dimensions. Ultimately, SSR and human security cannot be successfully operationalized in the absence of local ownership and participation.

- Understanding that Monitoring Mentoring Advising and Training (MMAT) are essential to the implementation of SSR mission mandates.

Facilitation Approaches and Methods: SME lecture presentation on the concepts and their applicability in the field of practices. Opportunities for discussions and comments should be provided. Use of some case studies will be useful in expanding personnel understanding of some of the complexities in operationalising local ownership in SSR missions. Class quiz would also be useful in enabling participants to have in-depth knowledge on these concepts.

2. To understand the local context within which they operate: SSR personnel are deployed to several locations often times in contexts that are different both physically and culturally. Thus, for personnel to effectively implement their mandate and enhance local ownership, it is important for them to:

- Understand the historical, political, and economic contexts in which they operate and how these factors interlink with the SSR mission

- Primarily become aware of their own differences, culture and values vis a vis that of the host country and how these influence behaviour and actions. Becoming aware of your own uniqueness and difference is important to acknowledging and respecting that of others

- Recognise the importance of accepting and respecting the existing culture, attitudes, values and practices within the local context

- Know that accepting and respecting values and practices in the local setting does not mean completely ignoring your own values but rather finding ways to maximize the commonalities and minimizing the differences (ENTRi).

- Understand some of the best practices and challenges to operationalising local ownership particularly in post conflict societies. The United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UNDPKO) highlights some best practices

Putting Local Ownership into Practice While the approach will vary depending on the specific context and activity, there are some general good practices that can be applied.

- Take a participatory approach and engage local actors at the earliest possible stage through liaison, coordination and consultation, gathering information about needs and perceptions, and engaging local stakeholders in planning processes.

- Channel information from the local level to mission headquarters about local constituencies and marginalized populations’ needs, concerns and priorities, and support the articulation of local grievances, interests and needs to inform national-level processes.

- Tailor the approach to the specific context and the nature of the activity by looking at local systems, structures, strengths, weaknesses and dynamics. Conduct regular analysis of the micro-level socio-political, economic and cultural context and calibrate the approach accordingly.

- Value and make use of local or “insider” knowledge and expertise, including that of National Professional Officers and local counterparts.

- Avoid undermining local capacity by “doing” or “replacing” rather than enabling: identify and build on existing processes and structures (informal and formal).

- Guard against bringing preconceived ideas or assumptions about what the problems or solutions are, for example by conducting joint assessments with local counterparts, by asking local stakeholders what they consider their needs or capacity gaps to be, or what they believe are the root causes of and solutions to conflict.

Facilitation Approaches and Methods: SME’s presentation should be integrated with role plays or simulation exercises. Here ‘Meme Awareness’ propounded by the PeaceTraining.eu could be a useful exercise (PeaceTraining.eu 2017). Case studies examples from the 13 EU SSR missions could be used in expatiating on how the organisation has been operationalising local ownership, the challenges and future prospects.

3. To understand the general mandate of SSR missions:

- Understanding of the core mandate and role of SSR missions. According to the EU Council, the core mandate of SSR missions are to among other things support: defence sector reform, police sector reform, judicial sector reform, financial reforms, border and customs sector reforms, demilitarize, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), as well as other general support (EU Council 2005, pp 13-16). Generally, these are implemented through channels such as capacity building, technical support and cooperation and advisory support to the receiving state (EC 2006; Bloching 2011).

- Understanding the principles guiding the implementation of such missions; which include local ownership; measuring progress; holistic approach; tailored approach and co-ordinated approach (EU Council 2005).

- Personnel become familiar with the areas of engagement with regards to SSR missions and their thematic focus.

- When possible, understanding the own mission mandate of to-be-deployed personnel with regard to the mission’s SSR objectives

Facilitation Approaches and Methods: SME lecture presentation on the various SSR frameworks. Allocating adequate time for discussions after the presentation will be very useful. Additionally, course assignments could be allocated to personnel to review and compare existing SSR frameworks. Adding reading materials on various SSR frameworks and legislations would be useful.

4. To understand the code of conduct for operations in such missions:

- Understanding and knowledge of the legal frameworks guiding SSR operations such as the Lisbon Treaty (2007), the Generic Standards of Behaviour for CSDP Operations (2005), Revised Guidelines for the Protection of Civilians in CSDP Missions (2010), International Human Rights Law, Code of Conduct and Discipline for EU Civilian CSDP Missions (2016)

- Understanding the process for seeking redress as well as the disciplinary channels

- Understanding the rules of engagement within the mission

- Understanding the Chain of Command/ the Command and Control structures within SSR field missions

Facilitation Approaches and Methods: SME lecture presentation on code of conduct and legal frameworks guiding SSR operations. Role plays could be used to demonstrate the channels for reporting and chain of command of the mission. Supplementary reading materials on the frameworks would be useful.

5 To have general knowledge of the competences essential for the implementation of local ownership: Implementing local ownership in any mission including that of SSR is admittedly a challenging task. This is because often times, it is difficult for personnel to be equipped with the adequate practical competences and skills as well as how to effectively utilize these competences in the field of practice. To effectively implement local ownership, personnel must be equipped with knowledge and capacity in various competences including but not limited to the following:

- Self-Awareness: Generally defined as the recognition of “one’s own personality and individuality” , self-awareness is an essential competency that SSR personnel need to acquire before, during and after deployment. Acquiring such competency not only enable personnel to be aware of their own backgrounds, views, perceptions, and interests and how they influence their work in the field but more importantly enlighten them on how they are going to manage their positionality in the face of contrasting views and values in the field. As Savin-Baden and Major (2013: 71) rightly underscore, being aware of their positionality, enable individuals or personnel to “interrogate their biases, beliefs, stances and perspectives”. In other words, recognising what makes you different and unique is a good starting point to acknowledging, respecting and accepting others’ differences. Self-awareness ultimately result in cultural/intercultural awareness where personnel becomes aware of and respects the diverse perspectives, values, and principles existing within the local context and how that shapes or influences their work.

- Effective Communication: Communication is a fundamental element in peacebuilding and by extension SSR. Having the skills to interact, articulate and transfer information and knowledge with clarity is a quality that is necessary for SSR personnel. In fact, the UN and other peace intervention organisation have underscored that while communication is vital, it continues to be a major gap in peace operations (UN Peacebuilding Support Office 2010). With most personnel deployed into SSR missions often from different backgrounds, orientation and language to that of the host country, communication becomes a challenge. Which is why it is important for personnel to learn how to actively listen, be aware of their body language and gestures, maximize communication tools within such setting to enable them to interact effectively with the various stakeholders. Some emerging tools for effective communication include Richard Salem’s Empathic listening (or reflective listening) which enables individuals to put themselves in others situation to understand their emotions, feelings and challenges in order to build trust, openness, and create spaces for “collaborative problem solving” (Salem 2003 ). There is also communication peacebuilding or communication for peace, a concept which enables individuals or practitioners to maximize existing and innovative communication resources to engender peace (SFCG and USIP 2011; Hoffmann 2013).

- Consensus Building: One of the essential roles of personnel is to enhance stakeholder dialogue and engagement in SSR missions. That is, contribute to improving collaboration and interactions within and among stakeholders as well as assist in mobilising different interest groups. To do these, it is important for personnel to be equipped with consensus building skills such as negotiation, mediation and facilitation.

- Cultural sensitivity: Acknowledging and respecting the culture, values and practices in field missions is essential to achieving sustainable peacebuilding. Similarly in SSR missions, it is important for personnel to be culturally sensitive to the different practices and values which sometimes, if not often, contrast their own views and opinions. For Snodderly (2011, p.17) cultural sensitivity is when individuals become “aware of cultural differences and how they affect behaviour, and moving beyond cultural biases and preconceptions to interact effectively”.

Facilitation Approaches and methods: SME facilitation on basic useful skills or competences for the implementation of local ownership. Tools such as the Bennett Scale for intercultural awareness, Empathic listening, communication for peace among others could be used as approaches to enhancing these skills. Enough time should be allocated for discussions and comments to enable participants to have in-depth knowledge and understanding of these basic competences. The use of role plays or simulation exercises would be useful in providing participants with practical tips on when and how to utilize these competences in the field of practice. Additionally, group activities or exercises could also be useful. Group activities such as ‘Elephant list’, ‘Just listen’, ‘blindfold game’ etc could be exciting and engaging ways for enhancing personnel’s communication skills (See Mindtools.com ; also see Garber 2008). Videos and online games could also be useful tools on expanding personnel knowledge on communication.

MODULE 2: learning objectives and training approaches

1. Understanding technical and political dimensions SSR: SSR is a technical process aimed at reforming (aspect of) a local security sector. This requires technical expertise often delivered by third countries (e.g. police, judiciary, military etc.). Yet SSR is also a political process, with several dimensions participants should know and be able to assess critically:

- An SSR process touches issues of political power in the home state and often has a sensitive nature. Changing the status quo can be considered a threat for some actors, both for legitimate and illegitimate reasons.

- Local ownership entails that the reform process is started by the local actors, while international actors lend support. In practice, however, international actors have own political interests that can undermine local ownership.

- Local ownership does not mean that the values of the international organization including democracy, rule of law, and human rights are sidestepped. Not all local actors will be committed to these values.

- Often many international actors, with different political interests and/or missions also play a role in the process