Search this section

METHODS

Methods are used to transmit, engender, or enhance particular learning objectives of a training. These learning objectives commonly include the development of competencies including attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Methods can typically be associated with particular training approaches. A prescriptive approach to training will commonly make use of lecturing, for instance, while an elicitive approach will make use of participatory methods such as group work.

Each particular method has strengths and weaknesses or challenges. Typically a training will make use of different methods. In the table, you find specific examples of methods that are used in the CPPB training field and links to further guidance on how to use them. While some methods are well-known, such as lecturing and group work, others are perhaps less familiar, including reflective interviewing and arts-based approaches. These methods offer promising avenues for peace training, however, which supports their inclusion here. If you are particularly interested in the use of digital technologies to enhance learning, please visit our E-innovations page!

| Method | Core principles |

|---|---|

| Lectures | A trainer or expert delivers a lecture with limited interaction with participants. |

| Group Work | Participants work together on a particular problem or task. They learn from each other, as well as how to work with each other. |

| Case Studies | In-depth analysis of a historical or fictional event. A case study allows training participants to investigate the workings of particular mechanisms and approaches in action by referencing real or fictional events. It is typically combined with other methods. |

| Role-Play | Role-playing is an experiential and participant-centred method of training in which participants assume different characters than their own in a given or created scenario. Role-playing is typically used to enhance skills development and foster (emotional) understanding. |

| Simulation | Simulation/gaming is an experiential method of teaching. The method enables trainers to immerse participants in a particular scenario they may encounter during deployment. They can practice their response to a situation and experience the effects of their response within the simulation. |

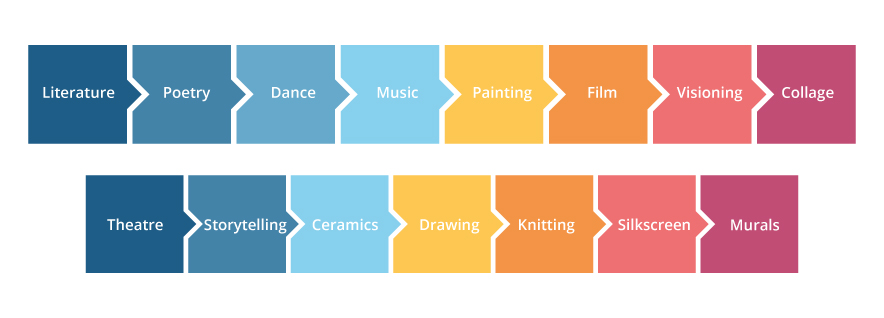

| Arts-based methods | Arts-based methods refer to learning tools inspired from arts and that utilise artistic mediums. Arts-based methods can be complex and powerful enablers of capacity building because they stimulate learning on multiple levels, including feeling, thinking and action. |

| Reflective interviewing | In reflective interviewing, participants ask each other carefully prepared questions aimed to create a learning experience by critically assessing and reviewing issues around their work, their own competencies, and experiences. |

How to select a Method?

PeaceTraining.eu recommends that trainers consider the following when selecting which methods to use:

- Methods should be diverse in order to cater to different learning styles and maintain the attention of the participants.

- Methods should be selected to match the learning objectives. Trainers may be attentive to whether the learning requires the development of attitudes, skills, or knowledge.

- Methods should be consistent with the PeaceTraining.eu approach, utilising adult learning theory and the elicitive approach.

- Methods should take into account group composition and group needs.

- Methods should prioritise the Five Sensitivities.

- Trainers should consider strengths of a particular method – What can this method do that others cannot?

- Trainers should be aware of pitfalls of specific methods and determine how to avoid them.

- Consider opportunities such as trends in funding schemes and new technologies (e.g. e-learning).

- Consider threats, such as obstacles/constraints to implementing a method appropriately (funding, bureaucracy, time).

- Trainers and training developers should be familiar with reports of best practices and lessons learned.

Introduction

Lectures constitute a presentation on a specific topic, undertaken over a finite time period. The standard length of time for a lecture on one subject in CPPB training in Europe is between 40 - 90 minutes, with many courses splitting between 45 minutes presentation, and 15 to 45 minutes for discussion or questions and answers). The lecture format, however, can be lengthened or reduced depending upon the need and content to be covered. Lectures / presentations (oral), are often visually supported by PowerPoint or (less frequently) prezi presentations. Additional supporting materials may include handouts, videos or other multimedia.

Lectures are the most common form of content delivery in many trainings in Europe today particularly in the military, police and state sectors. NGOs, private trainers and ‘front-of-field’ training institutions will usually use more interactive and practical skills and competency-based methods of training, while lectures may be retained for ‘briefings’, presentations of case studies, and focused delivery of core content such as lessons identified, key knowledge materials, and experience sharing.

The method of lecturing/SME’s fits with a prescriptive or transfer model of training, which ‘assumes that the expert knows what the participants need’ (Lederach, 1996; 48-49). Thus, the trainer/expert will often bring ‘packages’ built around his or her specialised knowledge and experience in the field of Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding (CPPB) - though good experts, even if using lecture-based delivery, will often evolve, adapt and customise their content and materials to the specific needs, learning objectives and contexts of participants. In this model, the knowledge flow is predominantly from trainer to receiver, with the knowledge of the trainer being a ‘key resource’, which is transferred to participants, who attempt to emulate it.

Lectures are often high in theoretical or knowledge / data content on CPPB facts (e.g. number of peace missions), issues (local ownership), frameworks (e.g. R2P or legal regimes for protection), procedures and structures, code of conduct, principles (e.g. Do No Harm), logistics / administration (e.g. mission support), lessons learned or identified and/or case studies and more.

Lectures are broadly arranged in 60 – 90 minute formats, though lectures can be reduced in size (see for instance TED Talks or subject matter briefings). Course participants may receive preparatory material to assist learning as well as follow-up and review materials after a session. This will either come in the form of readings (academic and non-academic articles), or multimedia (videos, talks, websites)

Lectures in CPPB may also incorporate ‘Subject Matter Experts’ or ‘SMEs’. Subject Matter Experts are often external to the organisation which is organising the training, but are specialists in their field. For example, EU personnel may give bespoke lectures in ESDC courses, a country specialist may provide a guest lecture to practitioners soon to deploy to a particular post conflict environment, or a national expert or practitioner may deliver key expertise on thematics, context or special issues relevant for that context.

Review of training methods and courses has shown that lecture and lecture-based delivery of subject matter expertise can play an important role in identifying key issues and transferring high amounts of important knowledge clearly. It is important to recognise, however, that lectures in and of themselves are insufficient as a methodology to develop actual skills and performance capabilities. For example: participating in a 60 - 90 minute lecture on mediation, prevention, early warning, peacebuilding, do no harm, or inclusion in peacebuilding may increase participants' awareness, knowledge and understanding of key issues, but will in most cases not result in development of actual capability to address - ‘do’ - these issues in the field.

Institutions providing training should be clearer and aware of the strengths and limitations of lecture-based delivery. While it retains value for some levels of knowledge transfer and information sharing and awareness raising, it is insufficient on its own for development of actual field / performance capabilities and competence. The use of lectures and subject matter experts in CPPB training may often therefore be best utilised in combination with more performance-based and skills and competence-development training methodologies.

- Lectures/SMEs allow for a rapid dissemination of key information to a wide audience. They are effective in being used in introductory stages of courses, as well as in the introduction of new topic areas.

- The lecture format ensures all participants have had the same access to a knowledge source. This is not to say that all participants have embraced the knowledge in the same manner, however it establishes a benchmark of knowledge received.

- Lecturing can introduce new theories/concepts in an quick manner. This encourages participants to develop their own understanding in their own time.The lecturing format introduces participants to Subject Matter Experts from other fields. This can be of great utility when a course is meant to cover a wide area of knowledge, incorporating geographic and thematic expertise, as well as institutional knowledge about the frameworks under which participants may be working.

- A lecture is heavily dependent on the presenter/SME. Therefore the views that are represented are filtered through his/her perspective.

- There may at times be the presumption of ‘universality’ of models and concepts lecturers are presenting. These should be checked for assumptions, applicability to context, whether they are in fact evidence-based and sensitive to diversity.

- Lectures may also lead to assumptions of what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’. Should a lecture/presentation uncritically outline a particular technique/approach, it may lead to participants assuming that the technique/approach is the ‘correct’ approach, whereas they may find it more difficult in practice in a more interactive environment.

- Inflexibility to change: at their most basic, lectures are relatively simplistic in their design (45 minutes talking, 15 minutes questions). This design can lead to trainers relying on this model, particularly when under time constraints at the preparatory stage.

- The format can limit the possibility of interactive discussion in the lecture. This however is dependent of the lecturer/SMEs approach and ability to engage participants during the presentation. For example should the instructor/SME speak for too long, then time limitations result in a lack of space for effective Questions and Answers sessions.

- The lecture format is reliant on the personality of instructor (particularly external SMEs). Should there be a challenge in the lecturer's’ ability to communicate information, then learning may prove to be problematic.

- Attention span can drop and retention of information delivered be limited after 10 - 15 minutes or less if the lecturer is not adept in how s/he delivers the presentation.

- Different participants have different expectations of what a lecture can bring. In larger group sizes, the chances of there being a wider range of expectations is heightened.

- There could be a language barrier between the instructor/SME and participants. This could have negative consequences on the chances that information is transmitted.

- Capability gap: It often does not equip participants with the relevant tools on how to develop and implement the knowledge transferred in the field of practice. Failure to recognise this ‘capabilities gap’ - the failure of a method to achieve performance competence on a subject matter - is why many lecture-based trainings fail to achieve learning objectives for development of actual competence and capability in participants.

The first question is to understand ‘why’ you are using a lecture. Lectures can be used as an effective way to introduce a topic, yet may be limited in providing a comprehensive overview of a topic area. If this is the case, how would lecturing fit with other forms of learning to deepen knowledge? In preparation for the lecture, the following points may be worth considering:

Learning objectives:

- Span of attention - Different participants will engage in different ways. In developing lectures ensure that they do not carry on for an extensive amount of time.

- Interactivity? It is worth asking ‘What level of interactivity do I want in a lecture?’ This relates strongly to how a lecturer/SME ensures that participants are engaged throughout the course. An idea - if employing an SME for a particular lecture - is to ask him/her as to how they wish to engage participants.

- You can also include a separate training with external SME’s on presentation skills, engaging the audience etc. before a training takes place.

- Participants may remember and understand the inputs of lectures (e.g. the frameworks, procedures and challenges of Security Sector Reform), but be aware that they often only reach higher levels of learning when they actually apply the knowledge actively in an exercise. Use lectures hence wisely, and interchange them with individual exercises or with participatory approaches like group work or role-playing.

- In a follow-up Q and A and discussion round, higher learning processes may be triggered depending on how deep/much participants engage with the input from the lectures.

- Avoid that the lecturer becomes the single source of authority by including different viewpoints in a lecture and supporting critical thinking (‘challenging the audience’).

Inclusivity:

- Be aware of diversity. Ensure diversity in the instructor/SME team in terms of gender, cultural background etc.

- Gender sensitivity is more than numbers! Lecturers/SMEs should take into account that the topics covered are discussed from a gender sensitive and inclusive perspective.

- Language issues. If the course is multinational, the level of the participants understanding will not be uniform. This may influence the use of technical terminology in the lecture. Additionally, the use of interpreters may be required.

- Participants from different educational and cultural backgrounds will have different ways to engage with a lecturer. For instance, some will feel more comfortable with a prescriptive approach, whilst others will be more comfortable with challenging the lecturer/SME. Additionally, some participants may not feel comfortable speaking in front of a large group. Thus, there is the need for the presentation to include diverse perspectives and utilise research and trainers from different cultures.

Content/Presentation:

- Content/Presentation structure. It is important for the lecturer/SME to think through clearly how the presentation is structured. They must ensure that the points they wish to make are clear. Illustrate with examples and references to concrete practice and contexts which participants can relate to. Ensure subject matter and use of examples have been crafted appropriately to the audience. Furthermore, to ensure effective engagement and interest of participants in the subject matter, there is the need to provide them with resources or reading materials to enable them time to prepare.

- Effective use of visuals and supporting materials can help but should not distract from the core presentation - also make sure not to have too much text if using slides as that can overwhelm participants and make them ‘switch off’. A flip chart is increasingly preferred over PowerPoint.

- Lectures may evoke participants’ experiences of working or living in conflict zones. Therefore care needs to be taken in the presentation of lectures, and use of photos, videos and multimedia in CPPB training in order not to trigger past or present traumas of participants. Key examples are the use of wartime videos or graphic display of sexual violence, to name a few.

Most, if not all courses surveyed in the PeaceTraining.eu Baseline assessment had at least some form of lecture/presentation aspect to them.

- Simply Psychology (2013), Kolb Learning Styles, Found at: www.simplypsychology.org, Accessed 12 April 2017

- Leeds Beckett University (2015), Skills for Learning: Kolb’s Learning Cycle, Found at skillsforlearning.leedsbeckett.ac.uk, Accessed 12 April 2017

- BBC (2010), Innovative teaching methods vs the traditional university lecture, Found at: www.bbcactive.com, Accessed 12 April 2017

- www.kcl.ac.uk

- Silver, Ivan & Ed, M. (2018). - INTERCOM - BEST PRACTICES MAKING THE FORMAL LECTURE MORE INTERACTIVE.

- Lederach, J. P. (1996). Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. New York, Syracuse.

- Wolter, S., Tanase, A., Brand Jacobsen, K. and Curran, D. (2017). Existing peacebuilding and conflict prevention (CPPB) curricula report. PeaceTraining.eu

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

Group problem-solving or group work is a training method in which participants work collaboratively on a common task. The use of group work as a learning method can be differentiated from lecture-based training in which a teacher transfers learning material to students in a predominantly unidirectional way. While lectures fit in with a prescriptive approach to training, group work fits in with an elicitive approach. Group work allows training participants to learn from each other, share valuable experiences, and practice valuable social skills, including active listening, interpersonal communication, and collaboration. As such, group work as a method also fits in with adult learning approaches or andragogy.

Group work can be implemented in different ways and for various objectives. The purpose of group work can be a brainstorming or brainwriting exercise in which participants are encouraged to come up with new creative ideas for specific problems. Such forms of group work tend to occur in small groups (4-6 participants) and have limited duration. However, groups can also be used for more extensive problem-solving tasks, including a technical exercise or the writing of a paper, which requires the groups to be formed for longer periods of time. The table below provides a short description of some well-known group work techniques.

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Brainstorming | A group of individuals attempts to come up with as many ideas as possible for a given problem. The discussion can be structured or unstructured. Ideas are spoken out loud and can be put on record or not. Keeping a log of the ideas uttered is generally regarded as most effective. In principle, evaluations of ideas are postponed to later group discussions. |

| Brainwriting | A group of individuals attempts to come up with as many ideas as possible for a given problem. Each individual first writes down own ideas and then notes are passed around. Other group members can build on others' notes to develop new ideas. |

| Fish Bowl | A group of trainees is divided in two groups. The ‘in-group’ is seated in a circle and discusses a particular problem. The ‘out-group’ surrounds the in-group and provides input on the debate at specific moments in time. |

| Jigsaw | Each individual in a group has the task of becoming an expert on a specific subject and instructing other members of the group on this topic. Input from all members is needed to complete the task. |

| Think-pair-share | Individuals first think on a specific problem or task by themselves and write down ideas. They are then paired to another individual. Both participants discuss the problem together. This technique can also be used for more than two group members. |

The group work method has substantial relevance for CPPB training. Within the field, there is increasing agreement that training participants learn better by learning from others’ experiences and that group work is beneficial to skills-based learning. This can be seen, for example, from the ENTRi and ESDC training approaches. Furthermore, many training organizations and trainers see group work from an instrumental perspective in that it fosters bonds between participants and supports the creation of expert networks:

“Training is one aspect, the network that you provide and help create is another is at least as important as contents of training”- Trainer

Group work in CPPB is commonly used to discuss the meaning of concepts such as ‘conflict’ or ‘reconciliation’, to provide input and different perspectives for conflict analysis, or to think of creative peacebuilding interventions. Group work is also commonly combined with the case study method, and the simulation and role-play methods.

The general benefits of group work lie in their potential to increase the learning speed and depth of training participants significantly. Lecture-based learning has important advantages, but is has often been criticized for failing to retain participants' attention long enough to achieve full learning transmission. Group work allows participants to discuss learning material in an active way with others, allowing for on-the-spot critical assessment and reflection. This participatory ‘learning-by-doing’ ultimately leads to higher learning levels. Furthermore, by working together in group, participants also learn important skills and attitudes including respect for diversity, intercultural mediation, active listening, and negotiation and mediation skills. These skills are highly valued in the CPPB field in which cooperation with different cultures and sectoral backgrounds is the norm (cf. multi-stakeholder approaches). Finally, group work helps foster the creation of networks in CPPB.

Group work has important strengths, but can also have substantial weaknesses. These weaknesses tend to be caused by negative group dynamics or insufficient task preparation. It is generally the trainer or facilitator’s task to carefully mitigate the potential weaknesses of group work, which include:

- Lack of participation, which can be due to social loafing/freeriding or shyness, and introversion. A facilitator can mitigate this by increasing individual responsibility in the task.

- Dominance by some can lead to a lack of participation from others and should hence also be mitigated. Dynamics to watch out for include: senior staff dominating over junior staff who may not feel comfortable to speak in front of them; men who dominate over women in groups because they feel more enabled/empowered to speak; western participants and international organizations dominating over national partners and non-western participants.

- Unclear task instructions: group work is only effective if everyone clearly knows what is expected from them in the task.

- Productivity loss: a lack of documentation of input, including which points and arguments have been raised in the group can lead to repetition and lack of creative solutions.

The following guidelines can be implemented to avoid the weaknesses of group work and foster its strengths:

Avoid weaknesses:

- Make sure participants are acquainted with each other and provide sufficient time for the development of relaxed and reciprocal relations between participants (e.g. icebreakers, informal activities outside of the classroom).

- Facilitators should be trained in organizing group discussions, encouraging input by all participants, and avoid tensions.

- Develop specific tasks and techniques to raise individual accountability in group work and avoid social loafing. The Jigsaw technique, for example, accords specific roles and each individual is tasked to provide input on a certain topic. The Brainwriting and Think-Pair-Share methods ask participants to first write down ideas before sharing. Writing down ideas individually can also be useful as it provides some time to participants for individual problem-solving.

- Task instructions are clearly written, if necessary divided in sub-tasks to be solved by the group. There are also clear time indications.

- Avoid productivity loss by providing writing material (flip chart, post-its), by giving someone the role to document the debate, e.g. the facilitator

- Make sure that the learning space fosters group work by making sure sufficient space and enough chairs, tables, writing materials etc. are present.

- Non-discrimination: while cultural diversity mimics situations in the CPPB working field and group work can aim at stimulating intercultural communication, there are potential risks to watch out for. For instance, certain groups in society can be discriminated against and these social patterns can perpetuate in group work, even if the method requires participants to be seen as equals. Similar to discrimination of certain cultural groups in group work, one also has to watch out for discrimination against women. For instance, it can occur that women get ‘pushed away’ in group work and their input is neglected. As gender equality is crucial in the work place and in the field, it should also be actively supported in training.

- Cultural differences can arise in how people approach participatory approaches and collaborative learning. Some cultures can be more comfortable with hierarchical than consensual decision-making styles, for example.

- Individuals within a group can also have different personality traits and learning styles. For some people, group work can hence suit them better than others. Introverts might prefer individual work over group work and will get mentally fatigued by group work activities. It is hence recommended to vary individual and group exercises in a training.

- Language skills can impede participation and in-depth discussion in group work.

Foster strengths:

- Know your participants: study their CVs so you can build on their knowledge and experiences in the course, but also so that you can use this information in the creation of groups. It can be useful to put individuals with different backgrounds together to demonstrate different perspectives and support learning from each other’s’ experiences.

- • Aim for a diverse set of participants in terms of organizational background, nationality, and gender to ensure maximum learning from different experiences, mimic diverse settings on the ground and, foster the development of respect for diversity and intercultural communication skills.

The following major CPPB networks require courses to include participatory approaches in their methodology, including group work:

- Europe’s New Training Initiative for Civilian Crisis Management (ENTRi), Berlin, Germany: www.entriforccm.eu

- European Security and Defence College (ESDC), Brussels, Belgium.

- Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), Accra, Ghana.

- Hmelo-Silver, C.E., Chinn, C.A., Chan, C.K.K. and O’Donnel, A., Eds. (2013). The International Handbook of Collaborative Learning. New York: Routledge.

- Isaksen, S.G. and Gaulin, J.P. (2005). A Reexamination of Brainstorming Research: Implications for Research and Practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 49(4), 315-329

- Miyake, N. (2007). Computer Supported Collaborative learning. In R. Andrews and C0. Haythornthwaite, Eds. The SAGE Handbook of E-learning Research (pp.248-265). London: Sage

- CAMP and Saferworld (2014). Training of trainers manual: Transforming conflict and building peace.

- Mishnick, R. (s.d.) Nonviolent conflict transformation: Training Manual for a Training of Trainers Course.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

A case study consists of an in-depth analysis of a historical or fictional event. As a scientific method, a case study is used to investigate particular causal mechanisms of interest, and it is typically rich in description and context. As a teaching method, a case study concretizes learning material which might otherwise stay on an abstract or theoretical level. A case study allows training participants to investigate the workings of particular mechanisms and approaches in action by referencing real or fictional (but preferably based on real) events. In principle, the case study method can be combined with a range of other methods, including lectures, group work, role-plays and simulations. In a lecture or presentation format, a trainer uses a case study to provide additional clarity on a specific subject, highlighting how certain mechanisms played out or issues were addressed in the case. The lecturer can also highlight multiple cases and explain why they are similar or different, or identify the key lessons and points to be learned from them -sometimes focusing on specific issues or ‘good’ and ‘bad’ practices relevant for the field.

In group work, case studies can be used in exercises in which newly gained knowledge in the course is put to the test of application on a case. Or, the method can be used as a ‘base-line’ to assess the knowledge and experience participants are bringing to a training, by having them engage with a case study prior to further content and method delivery. Typically, the groups engage with case studies either by i. coming up with a solution to a particular case problem; or ii. identifying specific lessons and what can be learned to improve and inform future practice from a case. In role-plays and simulations, participants take up specific roles in historical or fictional events and (re-)enact the case. This may be to exercise their capabilities to find solutions to specific issues or to benefit from experiential learning of how they perform in the situations and contexts being enacted.

The case study method is used in different ways in CPPB training. The use of concrete examples is one of the most important ways lecturers in the CPPB training field can share best practices in the field. Furthermore, they allow participants to pick up on the concrete cases, share their own experiences and critically reflect on their dynamics and outcomes. As befits adult learning, case studies concretize learning material and facilitate learning by demonstrating direct relevance to participants’ work contexts. However, to support critical analysis, it is important to emphasize the complexity of cases (e.g. violent conflict outbreak) and be sufficiently in-depth in the analyses to avoid simple black-white dichotomies. Case studies can also be used in group work, for example as the basis for a group discussion on the causes of the conflict and programming solutions, or in a simulation exercise such as the re-enactment of historical peace negotiations (e.g. Northern Ireland, Kosovo). They can foster cultivation and development of skills, knowledge, and attitudes. The difficulty and complexity of case studies or how they are applied can also be customized to the specific learning and competency objectives and qualifications of participants.

The main strength of case studies is that they:

- Concretize abstract/theoretical information and make learning material more tangible and hence relevant for participants.

- can increase learner engagement through selection of cases which are seen as relevant or have similarities in issues and context to those in which the learners are themselves engaged.

Case studies also allow participants to achieve higher levels of learning. For instance, from knowledge to understanding to critical analysis in a lecture-based format, and from knowledge to critical analysis to additional skills (e.g. negotiation, mediation, intercultural communication) in a group work context.

Some weaknesses of case studies include:

- Insufficient adaptation to the working contexts and experiences’ of the participants, reducing its relevance and learning potential.

- Use of overly artificial or superficial case studies - particularly when using fictitious cases. If the cases are not designed adequately for realism and closeness to real life contexts and experience, participants may find them superficial and this may reduce interest and engagement in the programme.

- Case studies may often themselves contain multiple biases - biases in favour of a particular conflict party; gender-biases with excessive focus on or exclusion of one gender; sectoral bias excluding roles and engagements of other key actors; and can reveal ignorance or prejudices in relation to the conflict. Case creators and trainers need to be particularly sure that cases are developed drawing upon the 5 sensitivities: peace and conflict; gender; culture; trauma and learning.

- Insufficient critical analysis in case studies. Especially in lectures, critical reflection from participants needs to be stimulated, for example with guiding questions, and time for group discussion. In group work, the views from different participants are brought up which can help foster critical analyses further.

- Use of time: as with almost any training technique and method, proper time needs to be given to engaging with the case study to learn effectively from it. Trainers may wish to provide some elements of case study materials to participants before the actual start of the training or engagement with the case study in a specific session. Time should also be given for proper review and debriefing, ensuring that delivery, presentation or enactment of the case study does not dominate and take away time from proper processing and learning from the case study.

- Clearly define which learning objectives and competencies you aim to achieve with the case study for yourself. This supports case study clarity and gives indications as to which points to emphasize and which points are less important.

- Clearly define which learning objectives and competencies you aim to achieve with the case study for your participants. This supports participants in identifying important versus less important aspects.

- Carefully determine whether it is best to address the case study in a lecture, group work discussion, or role-play/simulation exercise, and prepare accordingly.

- Avoid overburdening participants with unnecessary information on the case, but allow for sufficient complexity and challenge to the exercise.

- Be prepared to address additional questions from participants and make sure your own knowledge of the case is more extensive than the material used for the training. This is especially important when using case studies you haven’t designed yourself.

- Make sure your own knowledge of the case is sufficiently critical and includes different perspectives. Stimulate participants to do critical reflection, weighing different arguments.

- The learning material provided to participants must be sufficiently in- depth, multi-partial, conflict sensitive and critical to avoid that participants make simple categorizations and propose ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions, or develop/sustain prejudices and assumptions.

- It is important to acknowledge that the ‘truth’ about a case depends on the lens from which it is looked at: outsider/insider or UN/EU/AU/civil society perspective. To implement cultural sensitivity in case studies, the case study designer (this can be the facilitator or an external expert) needs to be aware of source-usage and allow different perspectives to feed into the case, in particular local perspectives. Having participants themselves actively reflect upon the lens from which the case is presented and their own lenses on the conflict - or on the conflicts they are involved in - can also help strengthen participants’ own ownership and competence to engage with cultural sensitivity

- A gender perspective can be mainstreamed in case studies by making sure that issues related to gender are addressed in the case itself. For instance, when discussing a conflict or a potential intervention (e.g. a DDR or SSR program), the consequences or implications for both men and women (and children) should be emphasized in the learning material. Case study exercises should stimulate participants to look for such information and discuss how solutions to the case problem are gender-sensitive. This ensures that participants internalize the need to conduct gender-specific analyses in CPPB. Facilitators may also specifically select case studies which illustrate or facilitate learning on key issues of gender, including gender-based violence, marginalisation and disempowerment as well as gender-empowerment and the gender roles of women and men in peace and conflict.

- Trauma sensitivity is particularly important when dealing with case studies as they have the potential to trigger traumatic memories and experiences with participants. Particularly if participants have experience from the field or are themselves coming from conflict contexts, materials and instances addressed in case studies may provide immediate or delayed triggering of traumatic experiences and symptoms including anxiety, aggression, fear, anger and stress. Trainers should proactively: review cases for potential traumatic triggering/impact; ensure they or others in the training team are available to professionally and responsibly address possible traumatic experiences of participants; transparently engage with participants to identify possible traumatic impacts and check in with participants if they are comfortable to proceed; engage with participants before the training to work through possible traumatic experiences which may be triggered through the use of case studies. If facilitators or any of the staff or participants in a training team notice or have reason to believe that a participant is having an immediate or delayed reaction to trauma they need to find appropriate ways to engage with the individual or the organisations or missions in which they are deployed.

- Learning sensitivity: Individuals within a group can have different personality traits and learning styles which can affect how they engage with case studies. Some may prefer reading and learning about case studies and lessons through individual study and reflection. Others may prefer dialogue and reflective practice and joint review and evaluation of case studies. Others will learn best through applied role plays and simulations. Trainers need to be aware of different learning styles within groups and find the best combination of methods and approaches to fit the learning and competency objectives and learning styles and needs of participants. Trainers should particularly look out for signs that participants may ‘disconnect’ from a certain technique or approach, of if some participants ‘dominate’ too much, and work to find inclusive and effective ways of supporting the learning needs of all participants.

- Make sure the case is relevant to participants’ own work. You can build on participants’ CVs or pre-training needs assessments to ensure this.

- Allow participants to use training time to share own experiences, highlighting similarities and differences from the case. This does not necessarily mean that participants are getting off topic, but can actually foster further debate, critical reflection, and learning, and improve participants’ ability to connect learning from the case study with their own roles and operating contexts.

- Provide sufficient time in the learning plan for participants to read into a case study if this is required.

- Ensure proper time is given to debrief and review so the full value of the case study can be drawn on.

- Consider providing additional, supporting materials after the case study has been done, either in the form of other case studies or supplementary materials which may support participants’ further learning.

Make sure you have reviewed the case in light of the 5 sensitivities:

The International Peace and Development Training Centre (IPDTC) engages extensively with case studies in nearly all of their trainings drawing upon a wide-range of actual cases (Northern Ireland, Kenya, Colombia) as well as specific issue-based cases (farmer-herder disputes; engaging with armed movements; working with trauma and survivors) and customises cases, simulations and role plays to participants actual needs and contexts.

Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), Accra, Ghana: Reintegration courses and Mewaliland simulation exercise (designed by Transition International).

ENTRi: Security Sector Reform course and ‘UN Supports Peacebuilding and SSR in Karina’ simulation exercise

- Best-In-Class Negotiation Case Studies You Can Use to Train. Harvard Law School, Program on Negotiation

- Public International Law and Policy Group. Negotiation Simulation Packets.

- Miyake, N. (2007). Computer Supported Collaborative learning. In R. Andrews and C0. Haythornthwaite, Eds. The SAGE Handbook of E-learning Research (pp.248-265). London: Sage

- Brynen & Milante (2012). Peacebuilding With Games and Simulations. Simulation & Gaming, 44(1) 27–35

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

“Acting is a very personal process. It has to do with expressing your own personality, and discovering the character you’re playing through your own experience” (Ian McKellen). Role Playing or Role-playing Games are an experiential and participant-centred method of training in which participants assume different characters than their own in a given or created scenario and engage in exchanges in character in the respective role. Role-playing, as a training method has as its main objectives: exercising the skills and experiences addressed in the role play, fostering improved empathy and understanding towards characters that emulate actors in conflict; enabling inter-personal or conflict-handling related skills, such as collaborative dialogue and problem solving; developing or identifying possible outcomes in a mission/conflict situation and gaining insights and reflection on one’s own possible biases, prejudice and influence in a conflict situation.

Whether short exercises (30 minutes to a couple of hours) or day-long activities role-plays follow the overall pattern of

- introduction to the method,

- familiarity with the character,

- the actual playing out of the scenario

- debriefing and analysis

Role Plays as a shorter, less-elaborated method than simulations are extensively used in peacebuilding and prevention training in various sectors (civil, military, academia, diplomacy etc) and with different target groups (children, youth, adults, multi-stakeholder groups etc.). Role Plays are used for different levels of participants’ experience as well as for different topics. For example, role-plays are included in training modules to cover topics such as:

- Intercultural/cross-cultural issues

- Mediation, negotiation, dialogue

- Diplomacy, peace processes

- Meetings and functioning of various institutions such as UN, EU, OSCE

- Nonviolent communication

- Nonviolent resistance

- Re-creation of timelines and historical events, settings and conflict analysis

A typical example is Marshall Rosenberg’s use of the giraffe and jackal, as symbols of violent and non-violent communication to engage in several demonstrations of the principles and steps of this method.

Figure: NVC role-play demonstration

Another example is the Reacting to the Past (RTTP) curriculum which was pioneered by Prof. Mark Carnes in the 1990s. RTTP “consists of elaborate games, set in the past, in which students are assigned roles informed by classic texts in the history of ideas”. Here, participants are given the platform to run the entire sessions with instructors advising, facilitating and grading their work. Unlike plays, in Reacting roles (or RTTP) there are no fixed scripts or outcomes, hence participants are allowed to develop creative ways of articulating their ideas either through speeches, presentations in order to convince their audience and instructors.

Examples of RTTP scenarios include:

- Defining a Nation: India on the Eve of Independence, 1945

- The Collapse of Apartheid and the Dawn of Democracy in South Africa, 1993

- Forest Diplomacy: War and Peace on the Colonial Frontier, 1756-57

- Mexico in Revolution, 1912-1920

- The Needs of Others: Human Rights, International Organizations and Intervention in Rwanda, 1994

Role plays are experiential and participant-centred. When working with Role Plays, the trainer can take the role of a trainer, facilitator or coach. When playing the role of the coach, the trainer engages normally in two-person role-plays and takes one of the roles challenging the participants to learn and practice the skills that are most important for the respective training. Most typical is to take the facilitator role, setting the context and then intervening minimally.

In classic role-plays, participants are introduced to a brief scenario and to their characters, then asked to ‘get into the character’ to reflect and understand that character’s way of life, the concerns and hopes, the relationships that he/she has in the community, the strong and weak points and the position, interests and needs with respect to the given scenario. Following the stage of getting into the character, some role-plays introduce a “ritual” or symbolic exercise where each participants is stepping over an imaginary line leaving behind their real-life name and personality and becoming the character.

The actual scenario is being played with minimal intervention from the trainer/facilitator for the agreed duration of time. Following the termination of the scenario and the conclusion of the scene, a similar ritual of ‘getting out of the character’ could take place and participants and the trainer go through the debriefing of the role-play. The debriefing could include methods such as “trust-o-meter” or “tensi-o-meter” (graphical visualization of the levels of trust, tension, consensus throughout the role-play, “sociometries" (quantitative measures for relationships and realities within a given group) as well as group discussions and sharing on different aspects of the role-play.

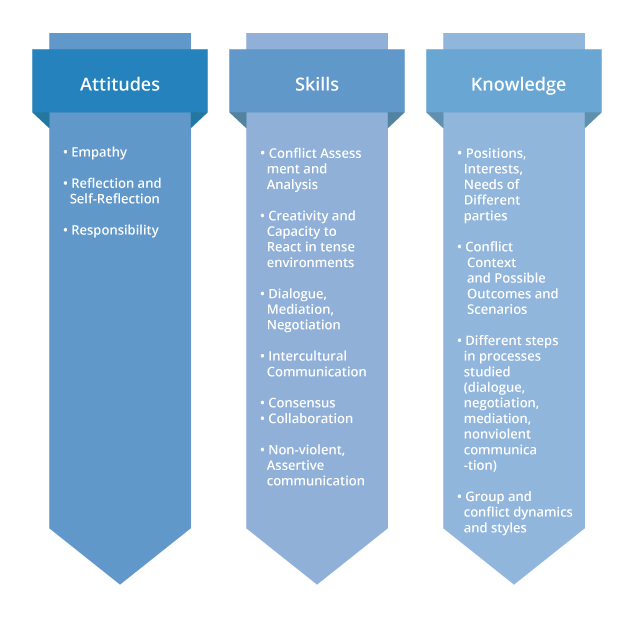

Role-playing leads to the following learning outcomes achieved include the following competences:

Figure: Role-play and ASK competencies

Also at the level of objectives, a trainer can aim at:

Most role-plays are face-to-face, although some could also happen virtually. Virtual role-playing games can be single-player and multi-player. In the single-player version, the player is controlling one or several characters, while in the multi-player version, the characters are distributed among different players.

- Powerful experience for the participants

- Both capacity building and possible research method; Role Plays do not only function as training method but also research method, enabling both the trainer and participants to note, observe and derive hypotheses on real dynamics of conflict and behaviour outcomes of different conflict parties, as well as on the effectiveness of different tactics and strategies of intervention

- Possibility to capture complex dynamics of conflicts: a role-play could include a large spectrum of conflict parties, different scenes and also allows participants to engage and experience the changing dynamics of a conflict situation

- Complete learning experience: the method allows working not only on elements of knowledge but also on practicing concrete skills and possibly enabling changes in attitudes

- At times participants may have difficulties to get into different roles

- Participants treat the role-play as a ‘game’ and exaggerate roles

- When not explored/ prepared thoroughly sensitivities towards different characters could influence the role-playing, including through the escalation of conflict

- Sometimes it is challenging to match the scheduling of the different sessions of a training with the unexpected dynamics of a role-play, thus having to end a role-play before it has actually reached the concluding phase

- Absence of some participants could negatively affect the outcome of the role-play and on-the-spot replacement could be challenging

To engage in effective role plays, trainers need to consider several aspects of using this method, in relation to the composition of the training team, the relation and understanding of participants’ profiles and also the process of doing the role-play itself.

Training Team Guidelines: When facilitating role-plays, the trainer can use a training team as observers/analysts or engage some of the participants in having observer roles. This way the trainer(s) can divide the task of observing the process and participants are ensured of feedback, also on an individual level; of note-keeping with regard to the process of the role-play; and of intervention where necessary if the process is derailed or reaches a deadlock. Especially when engaging as a coach, the trainer should be very aware of his/her own profile and possible biases with respect to the situation. Furthermore, the training team should avoid taking ‘power’ roles (such as the Chair of the meeting or the President of a certain country etc.)

Participants’ Profile Guidelines: In preparation of the role-play, the scenario and characters should be carefully weighed against the participants’ profiles. Particular attention should be paid to: participants who may have very similar profiles with the characters, and participants who may have experienced trauma and stress in relation to the situation described in the role-play. Even without a clear identification of such cases, in the briefing session the trainer should note and invoke the principles of confidentiality, volunteerism, signalling of discomfort/stress/trauma as overarching principles of the role-play as well as the availability of ‘safe zones’ and ‘trusted individuals’ throughout the role-play.

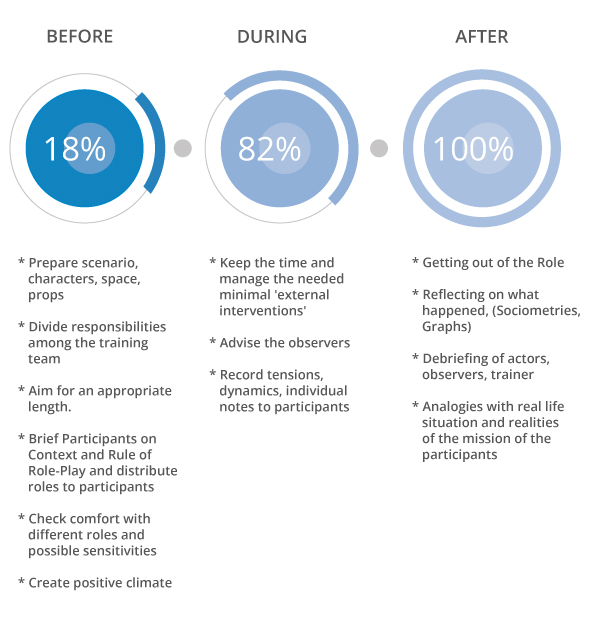

Process Guidelines: The following graphs introduces a succinct “TO DO” list for the trainer/facilitator throughout the role-playing process:

Examples of Role Plays:

- CMI: ahtisaaripaiva.fi

- USIP: www.usip.org

- How2Become Ltd: www.how2become.com

- Council of Europe: www.coe.int

- IREX: www.irex.org (Sample Role-Plays in the manual)

- Turning the Tide: turningtide.org.uk

- Jøn, A. Asbjørn (2010). "The Development of MMORPG Culture and The Guild" . Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies. 25: 97–112.

- Schuler, H.(1982). Ethical Problems in Psychological Research. Retrieved from books.google.ro : on 26/04/2018

- Barnard College. Reacting to the Past. Retrieved from: reacting.barnard.edu on 26/04/2018

- Brynen, R. Retrieved from: www.researchgate.net on 26/04/2018

- Brynen, R. (2012). Some Saturday afternoon thoughts on technology-enhanced role-play. PAXsims: Simulations—Conflict, Peacebuilding and Development—Training and Education.

- Retrieved from: paxsims.wordpress.com on 26/04/2018

- NVC Academy Youtube Channel. Retrieved from: www.youtube.com on 26/04/2018

- Peacebuilding With Games and Simulations. Retrieved from: www.researchgate.net on 26/04/2018.

- Shaw, C.M. (2004). Using Role-Play Scenarios in the IR Classroom: An Examination of Exercises on Peacekeeping Operations and Foreign Policy Decision Making . Retrieved from: pdfs.semanticscholar.org on 26/04/2018.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

Simulation/gaming is an experiential method of teaching. The method enables trainers to immerse participants in a particular scenario they may encounter during deployment. They can practice their response to a situation and experience the effects of their response within the simulation. Simulations replicate real-world conditions while allowing the participant to practice skills in a safe environment. They can be live, in person, in real-time or – increasingly – on-line. Simulation Design, Preparation, Implementation and Post-Simulation or after action debrief are four phases essential for effective use of simulations in CPPB training.

Simulations are increasingly recognized as an integral tool in CPPB training across the field. They can be used across all levels – from foundation / introductory programmes to specialisation and advanced or expert level trainings. They are used for everything from training for all terrain drive to handling critical moments in peace processes, supporting trauma recovery with refugees, or learning emergency first aid. Simulations – whether onsite or online – are immersive experiences replicating ‘real world’ conditions in the field. They are experiential. Participants engage in actual situations they may experience in deployment allowing them to improve their skills, knowledge and understanding and to test and challenge their responses, reactions to those responses and handling capabilities in the relative safety of a training environment.

Traditional simulations are carried out ‘live’ on-site where circumstances are created and participants experience the physical and psychological trials in real time. A recent innovation has been the use of computer-based single-user and online single or multi-user simulations. The term “gaming” is often used to describe computer-based simulations. While originally quite rudimentary, advances towards full immersion simulations are being made every day, and actors from the military to peacebuilding NGOs are increasingly turning to information and computer technologies to see how computer-based simulations can improve capabilities for peacebuilding and prevention.

In both off and online applications, simulation designers attempt to (re-)create realistic simulations to immerse participants in an as close as possible to real world experience. With rapid development of IT technologies, and the possibility to introduce artificial intelligence (AI) routines into the simulation and gaming applications, computer-based simulation/gaming activities for training purposes have become increasingly popular. This opens the potential for larger scale application of computer-based simulations as an integral pillar of future CPPB training. For example, the project Cultural Awareness in Military Operations (CAMO) is used as an “inexpensive and flexible games-based simulation for training cultural awareness for military personnel in the Norwegian Armed Forces preparing for international operations (Afghanistan).” The assessment at the end of such training has allowed the Norwegian Armed Forces to conclude that the understanding of culture and the performance of the trainees in the cross-cultural communication has improved, showing that such training method can be a valuable tool in developing these skills (Hernadez-Leo 2013, p.569). Such tools could be scaled for use more broadly across the CPPB field and for further integration of CPPB competencies and skills.

The simulation/gaming method is participant-centred. The participant’s active engagement with the simulation is essential for the success of this method. In addition, the participant’s role in debriefing is essential to consolidating learning. Substantial debriefing after the exercise can facilitate and consolidate this learning. The participant’s prior knowledge and experience can be of benefit when using this method, and the method is designed to be directly relevant to situations that the participant will encounter during deployment.

Learning developed through such simulations/games can fit into many areas of the competency model. They can be used to increase knowledge, to change attitudes and to develop skills, depending on the type of simulation used and on the amount of time given to reach the objectives. For example, in the simulation Virtual Afghan village, the trainees can increase their knowledge of the Afghan religious and cultural traditions and increase their skills in dealing with the local people in a culturally sensitive manner.

Some simulations facilitate a change in attitudes. Simulations can place participants either in the specific roles they are in or will face in the field, or in the roles of others they will engage with – whether partner organisations, other sectors, local or national leadership or communities. By placing participants in the roles of others it enables them to experience their perspectives, attitudes and issues they may be responding to in ways they might not otherwise. By placing participants in their own roles in simulated experiences, it can enable them to confront attitudes, assumptions and how they handle specific situations and relationships. This can help to address critical attitudes as well as possible prejudices and assumptions participants may have. This element is very important in CPPB missions where the conflict potential is high and populations may have well-earned mistrust of outsiders, or where the attitudes participants hold to different stakeholders, institutions or communities can affect their performance in the field. Participation in such simulations allows those preparing for the missions to better understand both their own perspectives and experiences and those they will encounter when deployed.

Virtual Afghan Village

The Cultural Awareness in Military Operations (CAMO) project of the Norwegian Armed Forces focused on creating tools for training inter-cultural communication and cultural awareness for the military personnel preparing for deployment to Afghanistan. For this purpose, the platform of the MMO (massive multiplayer online) Second Life has been used and a virtual Afghan village was created. The participants created avatars of the Norwegian soldiers and had to accomplish tasks which allowed them to exercise awareness, understanding and apply their skills in such a virtual setting. There were five goals identified: tactics (identifying threats based on the clues in the environment); gender (interacting with women in the communities); religion (dealing with religious customs); socializing (observing cultural customs); language (the basic language skills).

The use of this type of simulation showed that such a setting was very useful for the participants to learn the “soft” skills of communication and language, but, in this case, less useful for the understanding of threat-perception, partially because the virtual village was sparsely populated and partially also because the limits of the system for the reproduction of facial expressions and body language. Overall, however, the Virtual Afghan village simulation shows that with the limited resources and existing commercial platforms it is possible to create a computer-assisted simulation that allows immersion for the participants and teaches them the soft skills that will be necessary in their deployments. (Prasolova-Førland, Fominykh, 2013)

Simulations can be short term – sometimes even less than one hour – to multi-day simulations. They can be introduced as components of trainings utilising several methodologies or as a stand-alone instrument in which the simulation itself is the learning experience – together with preparation and de-briefing. In CPPB, where practitioners’ capabilities to perform effectively in the field are essential, simulations should be an integral component of any professional training and capacity building experience. Importantly: greater use of simulations to address core prevention and peacebuilding competencies is a vital frontier for the field. While extensive work has been done on using simulations for basic skills from all terrain drive to provision of first aid, and recent steps (e.g. the Virtual Afghan Village) have seen militaries expand to using simulations to teach cultural interaction skills, in the field of CPPB there is still tremendous room for improving the use of simulations – both on-site and computer-based – to improve key skills from peace and conflict analysis to mediation, problem-solving, counselling and trauma support, crisis de-escalation, dialogue, active listening and more.

- Simulations are one of the most effective means of immersing participants in real world conditions and experiences and testing their reactions to them. It can assist participants to not only ‘learn’ through receiving information and knowledge but to experience what they will face and develop both improved knowledge and greater intuitive understanding

- Simulations can help prepare participants for specific, actual processes. For example, mediators may simulate conditions of a peace process and possible risks and challenges they may face to help prepare effectively for a real-world process

- Simulations can be highly effective for addressing both consciously held attitudes and perceptions and those more deeply buried, which might not otherwise come out in non-experiential based courses. This can help to better prepare people for deployment

- Past traumatic incidents may be triggered through simulations while simulations can also help prepare participants for possible future traumatic experiences they may face in the field. Both, if conducted in the safety of a training process and with appropriately trained counselling support available can help improve participants trauma handling capacities and reduce risk in the field

- It works for both individuals and small to large teams

- It can help to test / assess individual participant’s readiness to learn, their profiles and interests and assist trainers to adapt and respond accordingly

- Computer-assisted simulations adhere to adult learning pillars and enable learning through practice and skill-building

- Development of IT technologies and commercial gaming allows constant improvement of the simulation/gaming tools, making the learning experience very close to the reality while in a safe context. This teaching method has an exciting potential in CPPB training

- Due the fact that IT systems can generate formative assessment, the simulation/gaming activities addressing the learning outcomes related with lower thinking skills and factual domain of knowledge can be conducted with the limited involvement of instructors and can be deployed to scale to improve basic level understanding and competencies of larger numbers in the field

- Just as addressing traumatic / post-traumatic incidents in simulations can be a strength, they can also be a challenge. Trainers and training support teams need to be sure to vet both simulations and participants for possible traumatic triggering or response, and be able to provide proper support as required. Even where trainers may not identify a risk of possible traumatic triggering, trainers and training teams should be prepared to handle this and support participants if such situations arise

- There are economic constraints as development of such a simulation/gaming platforms requires significant financial and intellectual investments. Should only governmental institutions be able to fund such platforms, content could be biased. There is a need to support more wide-spread development of simulations in the field but also the making of simulation platforms available to support CPPB training by a wider range of institutions and stakeholders

- ‘Inability to rapidly refine and adapt simulation-based content to address focused training needs’ (Benjamin, 2013, p.11). The group composition, size and target level of skills and capabilities for both live on-site and computer-based simulation training and video games may be pre-determined for the specific simulation, leaving limited flexibility for instructors

- Development of simulations, particularly quality simulations, is time and labour intensive. Many trainers in CPPB today are not themselves skilled/trained in development and use of simulations. In the absence of making simulations more widely available and in improving training and preparation of trainers for use of simulations, the potential for this method to be taken up and used effectively in training and preparation for practitioners in the field is reduced

- Simulations which are computer/IT based may have limitations for use in the field, as they can require quite powerful computers and access to high-speed internet

- Most of the simulation systems require fixed infrastructure and the training is conducted on site. Only few can be installed on PC and used to develop broad range of skills and capabilities

- There is a risk of needing too much time at ‘learning new systems instead of exercising decision making or critical thinking’ (Stoltenberg, 2012, p.47)

- The number of operating environment factors that can be incorporated and replicated by the IT system is huge. There is a risk that participants will develop broad-brushed idea of reality or the danger that capabilities developed in a gaming context may not be transferable by individual participants to real-life contexts and practice

We recommend that simulations are conducted with the guidance of an experienced trainer or training team. A training team with two trainers from diverse but complementary backgrounds may be particularly useful, as each trainer may have unique and relevant feedback from their area of expertise. Two trainers also allow the team to be gender balanced. A gender balance affords the opportunity of modelling gender equality.

Simulations are a complex teaching method and in both live and computer-assisted varieties follows through four broad stages: simulation design, preparation phase, active phase and the debrief phase.

The simulation design phase may be conducted by those involved in training delivery or may be carried out by training support teams prior to implementation. Computer and ICT-based simulations will also require computer programmers and design teams. Important in the design of simulations is to ensure they are as close to real world conditions as possible, or customised to test the specific skills, capabilities or attitudes they are designed for. Design of simulations can also benefit from input from practitioners from different sectors, genders and cultural backgrounds. Designers, particularly if coming from single sectors (for military, government or NGOs) may often be unaware of possible prejudices, ignorance or stereotypes they may unwittingly bring in to their simulations. The same may be true if only external or local input is provided into simulation design, or if only men or women are involved in the design. Simulations themselves should be tested to ensure they are appropriate and peace and conflict-, gender- and culturally-sensitive, intelligent and appropriate, and that they will not themselves ‘do harm’ in what they teach or promote.

In the preparation phase of the training, the trainer prepares the participants for the simulation. Trainers and training teams should think through what materials may be required for this – and simulations should describe clearly how to implement proper preparation. Preparation for simulations may include: development of role specific briefings and information packages for participants; review of case-studies or competency-related materials relevant to the simulation – through reading, lectures, exercises, reflective practice; safety briefings to ensure physical and emotional / psychological well-being during simulations, including clear guidelines on how to address possible stressors / traumatic issues. Trainers may specifically choose not to address this last issue in pre-simulation preparation and briefings if assessing how participants respond under stressful or possible trauma-impacting conditions is part of the purpose of the simulation. Participants need to be made aware of this beforehand for responsible practice and trained professionals or counsellors should be available to provide after action support. For computer-based / ICT simulations the trainer should assess the participants’ level of familiarity with ICT and with the subject matter and determines if any action is necessary to tailor the simulation to the participants’ needs or interests. The computer-based simulation method can appeal to those with different learning styles and levels as the level of complexity can be altered for the participant. The trainers should, however, get as complete an understanding of the participants as possible in order to facilitate such adjustments.

Simulations may be implemented in a single process – whether of short or long duration – or in several steps with preparation and debrief between each different phase. Simulations may also be repeated to enable participants to act upon reflections and learning covered in after action reviews. This approach to simulations can facilitate improvement and retention of attitudes, skills and knowledge and likelihood of being able to replicate good practice and avoid challenging practices in the field.

The active phase of simulation involves the participants in the particular roles in a set scenario or setting. It allows them to practice their skills and generate feedback throughout the process. In live simulations, the presence of trainers and their support throughout the process is thus necessary. In computer assisted simulations some feedback is generated by the system, though the “instructors monitor the progress and may also do some role-playing where necessary” (Taylor, Backlund, Niklasson, 2012 p.653-654).

The final stage of the training is the After-Action Review, where instructors collect and provide feedback related to the participants performance. There are many ways to facilitate after action review, reflection and learning. This may be instructor-led, participant-led or supported, or group-led or supported. Participants may also use instruments during the simulation, such as note recording, to support after action review – particularly if they will be expected to use this in the field. Training facilitators / instructors may also use system generated data, video recordings, or snapshots from the simulation exercise to visualise the key points. The use of “observers” may also be beneficial. These may be other participants, representatives of different institutions or organisations, veteran practitioners, local community members or others who monitor and observe the simulation and then provide feed-back, debriefing and review. Debriefing is an absolutely essential element to effective simulations and necessary to consolidate learning. The process should help participants to reflect on and deeply engage with what went well, what went wrong, why and what could be done differently. Here, participants may discuss stress of the simulation and what techniques worked in overcoming the stress. Trainers may then customise further rounds of the simulation, further training sessions, or further mentoring, coaching or counselling for participants to assist them in addressing key issues, opportunities and challenges.

The costs of the simulations vary extensively, but many simulations are too expensive for many groups. The large scale well developed live and virtual simulations can be of a prohibitive cost for the use of smaller training organizations. The prices of just the scenario of such simulations can range between 25.000 and 60.000 euros, not counting the training of the trainers. Simulations that teach “soft” skills can be cheaper, as the trainers can develop them themselves or, in case of computer-assisted simulations, use the existing platforms for their development, as the example of Virtual Afghan Village above shows.

Finally, computer-based simulations rely on proper infrastructure to support its use. This includes computer equipment and internet connectivity. Difficulties in obtaining this infrastructure may make it difficult to carry out this method.

Simulations are widely used by military in pre-deployment / pre-mission training and in humanitarian and development sectors. Since the early 2000s they have been increasingly implemented in CPPB training, particularly in mediation and negotiations trainings. There is significant potential for the much wider adaptation and use of simulations across the CPPB field.

- Benjamin, P., (2013), Using Simulation based Training Methods for Improved Warfighter Decision Making

- Brynen, R. & Milante, G. (2013). Peacebuilding With Games and Simulations. Simulation & Gaming, 44, 27-35. DOI: 10.1177/1046878112455485

- CRISP. (2016). Simulation Games in Non-Formal Education. Retrieved from crisp-berlin.org

- Hernadez-Leo, D., (ed,), (2013), Virtual Afghan Village as a Low-Cost Environment for Training Cultural Awareness in a Military Context, (EC-TEL 2013)

- Garris, R., Ahlers, R., Driskell, E., (2002). Games, Motivation, and Learning: A Research and Practice Model

- Griffiths, M., (2002), The educational benefits of videogames, Education and Health, Vol 20, No 3 Huntemann, N., (2009), Joystick Soldiers: The Politics of Play in Military Video Games

- Kolb, A., Boyatzis R.E., Mainemelis C., (1999), Experiential Learning Theory: Previous Research and New Directions

- Romanovs, U. (2014), Professional Military Education. Appreciating Challenges of the Learning Environment, Security and Defence Quarterly. ISSN2300-874.1 No 4/2014.

- Sabin, P., (2012), Simulating War. Studying the conflict through simulation games

- Stoltenberg, E., (2012). Simulations: Picking the right tool for training. Infantry; Nov/Dec

- Taylor, A., Backlund, P., Niklasson, L., (2012). The coaching Cycle: A Coaching-by Gaming Approach in Serous Games. Simulation & Gaming, 43

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

For reflective interviewing participants pair up and interview each other with a set of questions relevant to the course objectives. The interviewing takes about 1 hr (30 min per participant) and about 20-45 minutes are needed for de-briefing. It can be done for any group size. The trainer/facilitator just needs to prepare questions, building upon course content and learning objectives. To empower participants and let them guide and own the process, they can be asked in prior group work to develop those questions themselves.

Reflection is crucial for competence development as well as attitude and behavioural change. Reflection methods enable and empower participants to link prior experiences or possible future tasks with the learning / training experience. Reflection is the "ability to question one’s own behaviour, to keep a critical eye on one’s own strengths and weaknesses and to use the conclusions to guide future action (...) is a pivotal component of competence development." (Krewer and Uhlmann, 2015, 34). In reflective interviewing, the questions asked trigger a participant’s critical assessment and review of issues around their work, their own competencies and experiences. The objective of reflective interviewing:

- is to initiate reflective / transformative learning, as participants connect personal competences, attitude and past experience in conflict prevention and peacebuilding work with learning experience in training

- that participants critically reflect upon certain topics / issues relevant to their mission environment, tasks, responsibilities, aspects of motivation, mission context, as well as personal strength, opportunities and challenges

Outcomes can include:

- Increased awareness and sensitivity towards a certain topic, e.g. conflict, culture, gender, intercultural communication

- Attitude change towards a certain topic

- Behavioural change, e.g. in communication and cooperation with local partners

Other methods to facilitate or enable reflection in training can include Individual Reflective Practice:

- Journaling (also online e.g. blogs)

- Learning Portfolio (learning notes)

- Essay (also online)

- Video (especially online)

- Painting, Poster

- Photo collage (also online)

- Reflective walks

Supported Individual Practice:

- Mentoring / coaching through trainer

Reflective Practice in Pairs:

- Interviewing (also online, via Skype or another online calling / video programme)

- Painting, Poster, Photo collage

- Theatre, role plays

- Experience sharing

Reflective Practice in Groups:

- Painting, Poster, Photo collage (also online)

- Theatre, role plays

- Open discussion (also online)

- Guided discussion / Focus groups / Reflection Circle (e.g. with questions from trainer or participants themselves) (also online)

Methods for reflection can enhance peace training through providing participants with the opportunity to experience attitude change, promote skills development, and synthesize knowledge. If well planned and implemented as well as openly received by participants, reflective interviewing can:

- raise awareness on issues and challenge personal biases and perceptions

- sensitize and stir critical thinking, attitude and behavioural change about issues like cultural and structural violence, local ownership, do no harm, personal stereotypes and biases, (intercultural) communication pattern, conflict sensitivity, gender, cultural and ethnic diversity etc

- assist participants themselves to internalise reflective practice as a key skills in peacebuilding and prevention

- This exercise can be adapted to any group, topic or sector in peace training, because the trainer has the freedom to create the questions, fitting the audience and learning objectives. Depending on those questions, the exercise has the power to stir problem, self-, method and communication/cooperation reflection

- Reflective interviewing is participant-centred and the reflection process controlled and owned by each individual, so that it fits with the principles of adult learning

- The training experience is directly linked with the working realities of the practitioners

- In reflective interviewing, every participant gets to speak, ask and answer the questions. Shy or calm participants get a space to talk and reflect, who might have remained silent in a group reflection exercise

- Participants get to know each other better and thus a positive learning atmosphere can be fostered

- The interviewing fosters active listening and communication skills

- Furthermore, the interviewing can be done in a way that is conflict, culture and gender sensitive – it all depends upon the interview questions